Only Four Exercises? A Confession to Make

I've got a confession to make. But first, I need to briefly touch on something..... You know the 80-20 rule, aka, the Pareto Principle? You know, the phrase which states that, for many events, 80% of the effects stem from 20% of the causes? I've referenced the 80-20 rule in my writings before to hit on the point that, within the sphere of physical training, 80% of your results are going to stem from 20% of the exercises/modalities you choose.

For example, let's say we have Person A and Person B. Both A and B possess identical genes, have the same training history, etc. etc. etc., and we have each of them perform the following workouts:

Person A: Squat --> leave gym Person B: Squat --> romanian deadlift --> lunge --> reverse hyper --> lying leg curl --> leave gym

I'm willing to bet that if you were to compare the results of Person A and Person B, the results of A would be pretty darn close to B. In fact, in some cases, the results of A may be even better than B.

Which leads me to my confession: Many times I will give my athletes and clients new exercises solely for the purpose of keeping things "fun" for them, as opposed to doing it because it's intrinsically necessary for their success in the gym.

"Woah, woah, WOAH there Mr. Reed, shouldn't you always do what is best for your hard-working athletes and clients?" you are probably asking me right now.

Well, in a way, I am giving them what is best for them.

You see, there are a couple little facets of human nature pertinent to this discussion. I like to call one of them "boredom." The other characteristic is something I like to refer to as "always looking for the silver bullet" (not as concise as the first one, but I hope you catch my drift). It's the very reason why the popular fitness magazines continue to sell. Because the editors are smart, understand how to prey on human nature, and know that if they place just the right promises on the cover, then their magazines will fly off the shelves like water during Y2K.

And the strength coach walks a fine line between managing these elements of human nature (i.e. continuing to give the athletes enough variety to keep them interested in their training), and giving the athletes what they need for success (which may be just doing 1-3 exercises per day, albeit manipulating the volume/intensity throughout the training cycle).

If the athletes aren't having fun, they aren't going to want to come back to train. If they don't want to come back to train, then when they do show up to train (because their coach/parent tells them to, or because they do it for the same reason they know homework is good to do), they are going to do so begrudgingly and give a half-hearted effort while in the gym. And then everyone loses out anyway.

It's a similar concept to general fitness enthusiasts. If they don't believe their program is going to give them more sculpted arms, or reduce their body fat, then these things probably won't happen! If they DON'T BELIEVE that they won't reach their goals without constantly doing new exercises, and making things as hard as possible (if it's not hard, it can't work, right???), then they'll be lucky to see their desired results anyway.

This actually reminds me of when we prepared Jason for his selection and assessment with the US Special Forces. After his first wave of training, he approached me and, to his credit, was very honest and blunt and expressed to me his concern about a few things in his programming.

In essence, he doubted that what we were giving him was actually going to get him from Point A to Point B.

I looked at him, and responded with, "If you don't believe in the program we are giving you, then it's not going to work regardless. Trust that what we are providing is going to help you succeed, and you will succeed."

Needless to say, he nodded his head and from that moment on grabbed the bull by the horns throughout the remainder of his training. You can discover the end results of his training by reading his testimonial in the link above.

Anyway, my point in all this is that oftentimes we get so lost by majoring in the minors, that we forget the "bread and butter" of what makes our training a success. For me personally, I've found that by focusing on four exercises at a time give me the best results. And every time I try to add more, it causes me to stray off the straight and narrow path toward my goals. For the past 10 weeks, these four exercises have comprised 95% of my training time:

1) Deadlifts 2) Inverted Rows 3) Sled Pushes 4) 1/2 Kneeling Landmine Presses (perhaps the only "press" variation I've found that has yet to irritate my cranky shoulder)

And you know what? I've continued to get stronger, and I've never felt better.

So I guess I'd revise the Pareto Principle to say that, in the realm of physical training, it's more of a 90-10 rule or, heck, even a 95-5 rule. There are of course exceptions to this, and no I wouldn't have a beginner perform only four exercises per training cycle.

I was kind of all over the place in this one, so let me try to best sum up my points:

1) Less is more. A very small percent of the exercises you choose (assuming you choose them wisely) are going to be responsible for the large majority of your results. 2) Even though #1 is true, sometimes the strength coach has to throw the athletes and clients a bone (or three) to keep them interested/having fun. Training should be fun, and even if my programming is partially motivated by helping those under my watch enjoy training for the sake of training, then I see nothing wrong with this. After all, not everyone gets off to doing inverted rows ten weeks in a row. 3) I'm not saying that one never needs to do direct ab or arm work. Don't be silly. 4) If you don't believe in the program you're doing, then it's not going to work, no matter how "perfect" it is.

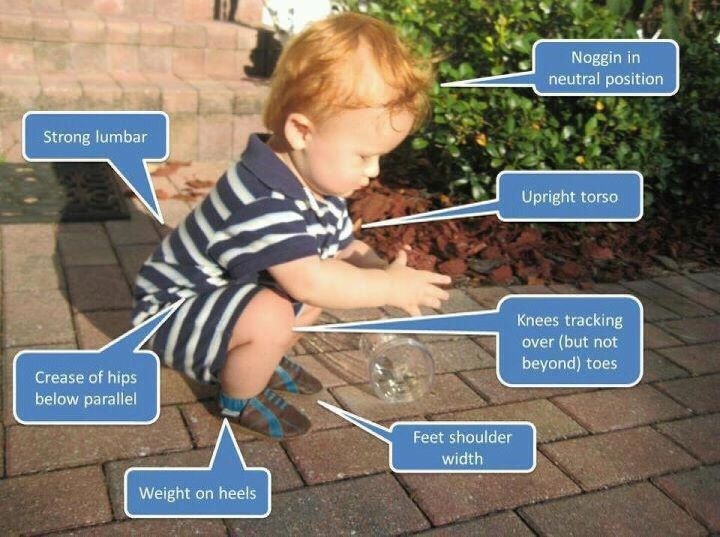

Are You Really Squatting Correctly?

We all know the cue of “drive your knees out” when squatting but have you ever had someone observe your squat or watched yourself on camera when squatting? If you haven’t you’d be surprised to find out that your knees are probably tracking incorrectly. When coaching the squat to our athletes and clients for the first time I notice two things that happen. The first thing is the knees just do not drive out at all leading to improper tracking and you get something that looks like this…

[vsw id="AabLx4YvJvg&list=UUKSYQ75Buogznl62rdbks2Q&index=3&feature=plcp" source="youtube" width="425" height="344" autoplay="no"]

As you can see from the video the knees never track with the middle of the feet and you are left with a continuous valgus collapse. This is due to a number of reasons (poor glute strength, lack of body awareness, tight adductors) but mostly because people grow out of the habit of squatting correctly because they simply stop doing it over the years. Yes, it is true that if you don’t use it you lose it. We all at one time possessed the ability to squat correctly we just don’t do any up keep and then quickly forget how to do it.

Anyways, after seeing this I'll tell the person for the next set that as they lower they need to actively drive their knees out or “towards the wall”. This is when I notice the second thing that typically goes wrong during a squat which you can observe from the video below.

[vsw id="_Vuw15qlRfg&list=UUKSYQ75Buogznl62rdbks2Q&index=2&feature=plcp" source="youtube" width="425" height="344" autoplay="no"]

This time you’ll see that yes the knees actively drive out but they drive out way to much at the beginning, they will shoot in as they get close to the bottom, then will shoot in once they switch to the concentric portion. Cue face in palm…

So what do you do now? When it comes to this I will simply ask the person what they feel is going on with their lower body throughout the movement. Undoubtedly they will say it feels weird or it feels like they are actively driving their knees out. I’ll go on to tell them what is actually going on and/or film them to show them. Most of the time I don’t need to film because I will explain what I want to see happen on the next set. I'll say, “On the next one I don’t want you to drive your knees out until you feel you are half way down. Once you feel you’re about half way I want you to really overcompensate by driving your knees out about twice as hard as you feel you need to”. What I’ll get out of this is exactly what I was looking for which is the knees tracking with the “middle” toe of the foot throughout the whole movement as you can see in the video below.

[vsw id="OoqbgRL_0XA&list=UUKSYQ75Buogznl62rdbks2Q&index=1&feature=plcp" source="youtube" width="425" height="344" autoplay="no"]

It’s amazing how well this has worked but also a little crazy. It takes someone literally trying to overcompensate twice as much from what they think “feels right” in order to get them to squat correctly. I’ll ask the person how that felt and they will always say “really weird!” My immediate response is well that’s actually exactly what it should look like and eventually the more you do it the more it will start to feel right.

I encourage you to have someone look at your squat who knows what they are doing or have someone record you so you can make sure you are squatting correctly. If your knees aren’t tracking correctly you probably won’t get much stronger and you will also be setting yourself up for injuries later on.

Hope this helps!

Straight Bar vs. Trap Bar Deadlifts, Part 2

In Part 1 we discussed the main differences between deadlifting with the trap bar vs. doing so with the straight bar, and also examined the primary muscles recruited through each pull. Part II will touch on some of the training implications - aka the, “How does this affect ME?” question. I like lists, so what follows are, in list form, some key points surrounding each deadlift variation.

The Trap Bar

1. I previously stated that the trap bar tends to be easier to learn how to deadlift with, and while I still stand by that claim, it doesn’t mean the trap bar can’t be royally screwed up if unaware of what to feel or look for.

Continue Reading....

(Note: The above link takes you to my most recent OneResult Article)

Q&A: Strength/Power vs Hypertrophy/Size?

Pardon my ignorance, but what is the difference between training for strength/power and for hypertrophy/size? It seems that if one becomes strong enough to squat 400 pounds or bench press 300, they are not going to be small and weak?

J – Thanks for the question. This is actually a great question that I don’t believe many people ever consider. It also touches on some of the fine points of programming and why – in my (not-so-humble) opinion – SAPT really excels at program design and getting our clients to their goals.

Your assumption that if someone is able to squat X and bench Y they will not be small and weak is basically correct. BUT, to get them to those goals you have to begin complementing the heavy compound or main movements with accessory and supplemental work that will effectively support the needed growth to hit those heavier maxes. When I say growth, I am referring to both neural growth/adaptations and actual muscle hypertrophy.

If one were to stick with a strict maximum strength development program they would be missing out on the strength and hypertrophy spectrum. The result would be very little hypertrophy because the volume will be so low… even though the weights will be very heavy. The primary result will be neural adaptations. As a side note, this is the style training I use with my college teams when I only want performance improvements and very little gain in weight or size: maximum strength, strength-speed, speed-strength, and speed methods.

On the other hand, if you begin to carefully combine the maximum strength work with some hypertrophy and strength set/rep ranges then you will be able to simultaneously (and very efficiently) gain the needed muscle to support the improved neural functions.

Hope this answer helps clear things up!

A Tool for the Toolbox

An awesome aspect about being a strength coach is you get to watch great coaches do what they do best and at the same time be taught by them yourself. You have the pleasure of learning and then applying this knowledge gained to your athletes and you alike. The following deadlift refinement technique is not something I made up; again it’s something that I learned from the awesome coaches I’ve worked with and something I’ve been able to utilize with the athletes and my own training. Try this to fix up your deadlift technique… The volume is a little low for some reason (my apologies); better than last time though…

[vsw id="E44ocLkSOu0&list=UUKSYQ75Buogznl62rdbks2Q&index=1&feature=plcp" source="youtube" width="425" height="344" autoplay="no"]

A few supplementary notes…

- This is not something to go super heavy on. This is a tool to refine your deadlift technique.

- Keep the bar weight light but use bumper plates; as I mentioned in the video it was only 95lbs of bar weight.

- As far as band tension goes you shouldn’t be using anything more than a mini band.

- Use this during your warm-up or during your off days as a way to improve your form.

Also the below video is definitely worth checking out if you’re looking for some motivation before going to train. The video is of Jeremy Frey, a strength coach and powerlifter from EliteFTS. This guy is ridiculously smart when it comes to training and STRONG!

[vsw id="4WAkvOnZv7w&feature=player_embedded" source="youtube" width="425" height="344" autoplay="no"]

3 Tips to Improve Your Bench Press

I'll get straight to the point with this one. Everyone loves to bench press including myself but very few do it right. Why do something unless you're going to do it correctly? Try these simple tips to improve your bench. 1. If you don’t set up correctly your bench will suffer…

I’ll walk you through my set up; keep in mind you don’t have to do it exactly like this but I have had success with it and I feel I get tighter on the bench than most people. Start with your chest under the bar and set your feet, this becomes your first base of support (I choose to leave my heels on the ground). Leave your feet in that position as you slide your body through; while sliding through start to arch your thoracic spine and pull your shoulder blades back and down (retract and depress). Once you are in this position push your upper back and head into the bench while keeping your butt on the bench; these become your other base of support. Congratulations you now have a good set up and if you are doing it correctly you should feel extremely uncomfortable; almost cramping in your upper back it’s so tight. Do this even in your warm-ups, I don’t care if its 115lbs or 315lbs each set up should be the same.

[vsw id="qtn5tEqsjqE&list=UUKSYQ75Buogznl62rdbks2Q&index=1&feature=plcp" source="youtube" width="425" height="344" autoplay="no"]

2. Always have the intent to move the bar FAST!

I feel like this is a no brainer but I guess not. You need to go fast and if you’re not fast then at least try and go fast (that would be me). Having this intent to move fast during the CONCENTRIC portion (upward portion) is going to recruit higher threshold motor units allowing you to accelerate with more force thus getting you stronger. So your press should be nice and controlled on the way down, quick pause on the chest and BOOM! Lastly, if you are grinding out reps then you aren’t moving fast so you should oh I don’t know, DROP THE WEIGHT! I just wanna go fast!

3. Do upper back work….. All the time

I don’t care if it’s an upper body day or a lower body day, you should be doing some kind of upper back work every day. A strong back will help your bench press. It’s going to allow you to get tighter on the bench, control the eccentric better, and utilize your lats more. Right now my upper body days consist of two horizontal pulls (any type of row variation) ranging from 3-4 sets of 10-12 reps and my lower body days consist of a vertical pull (lat pull down, pull-ups, neutral grip pull-ups) and scapular retraction work (banded W’s or band pull-a-parts) usually in the 30-50 rep range and I break it up however I want depending on how I’m feeling that day.