Breaking Down The Broad Jump

In the second portion of our football testing series we will take a look at the standing broad jump. This test is a fantastic assessment of lower body horizontal power. This tool works great for football players, who have to explosively move of the line of scrimmage once the ball gets snapped. A common misconception is that you merely stand on a line and jump. Don’t be fooled by the simplicity of this assessment. Horizontal jumping can be a complex coordination pattern because the upper and lower extremities must move harmoniously in order to achieve optimal results. Let’s take a look at a few factors that can help you or your athletes add a few inches.

The Arm Swing

It’s no surprise that lower body power is what propels you forward during this test but the arms play a vital role in projecting you higher off the ground and further down the tape measure. The most efficient swing technique would be to start in a standing position with your arms out in front of you. As you drop down to “load the spring” your arms should sweep back, followed by an immediate, powerful swing forward as you takeoff.

http://youtu.be/lqc_pyG7ELk

Build Those Glutes

The hip complex packs a lot of useful muscles that are crucial in just about every sport and activity of daily living. Unfortunately, many people do not train this area of the body as much as they should. We often sit in chairs, whether at school or work, and that equates to hitting the “off” switch for this important muscle group. Driving through hips during the jump and getting this area fully extended will propel the athlete further. Simple hip extention exercises like glute bridges, whether bodyweight or weighted, will help bring life back to your butt. Below are a couple videos to help with the exercise selection:

http://youtu.be/pMQV6A8F8Qw

http://youtu.be/8j4kWFHRq9o

Own The Descent

Does it matter how awesome the take off was if a plane crashes near the end of its flight? The same theory (obviously to a lesser extent) holds true during the broad jump test. Height and distance are all based upon the action taken prior to take off but this in no way omits an individual from having to properly land each jump. When landing a jump it is important to land in a position that allows the force to dissipate. This is achieved by bending the knees and sinking back the hips. An athlete should never land in a stiff-legged position. When landing, it is also important that the knees land in a position stacked in-line with the ankles and do not collapse or cave medially. Both of these habits place a high amount of stress on the joints and can lead to serious injury. Below is a chart with normative data to see how football players stack up in this test and other common tests by position. Check back next we as we move on to discuss the bench press.

References:

Lockie, R. G., Schultz, A. B., Callaghan, S. J., & Jeffriess, M. D. (2012). PHYSIOLOGICAL PROFILE OF NATIONAL-LEVEL JUNIOR AMERICAN FOOTBALL PLAYERS IN AUSTRALIA. Serbian Journal Of Sports Sciences, 6(4), 127-136.

5 Not-So-Common Tips on Finding and Cultivating a Mentorship

When pursuing excellence in a particular discipline - athletics, business, academics, music, “life” in general, you name it - finding and procuring a mentor to guide and sharpen you is not a nice-to-have. It’s a must-have.

I’m not going to delve into the why of the matter, however, as I believe you already know the why.

Besides, if the one and only Gandalf had mentors during his time on Middle-earth, then you and I both need them during our time on Regular-earth. The equation is simple.

Now, while the why may be simple, the how is a different matter entirely.

Many individuals recognize the supreme value of mentorship, but often feel stymied in their attempts to actually make it happen. This could be due to a variety of factors: lack of direction (“where do I even begin?”), fear of being turned down, or, quite frankly, laziness.

In my own life, while walking down the path of attempting to identify suitable mentors and enter into fruitful relationships with them, I’ve made no small number of mistakes. Fortunately, these mistakes have birthed many valuable lessons and insights which have enabled me to, eventually, experience some pretty amazing and invaluable mentorships that I am forever grateful for.

Here are a few fundamental principles and essential ground rules that I’ve picked up during my own personal journey.

1. It’s not necessary to find the highest-level expert in the field

Say what?

This statement may catch you by surprise. After all, why wouldn’t you want an unrivaled expert in your field of interest to be the very one who personally teaches you, nurtures you, guides you, challenges you during the process of honing a specific skill set or discipline?

There are many answers to that question, but one of the most important is this: they may not be the best teacher.

[As an aside: while mentor and teacher are not synonymous, all mentors are teachers to some degree, which is why I raise this point.]

The interesting thing about true masters of a specific domain, is that they’ve been so deeply intertwined with the subject for so long that the fundamentals, the critical information that a beginner must learn during the early stages of skill acquisition, have become so deeply internalized that these basic principles are now seamlessly integrated into their actions without even having to think about them.

As Josh Waitzkin aptly put it, the foundational steps are no longer consciously considered, but lived.

“Very strong chess players will rarely speak of the fundamentals, but these beacons are the building blocks of their mastery. Similarly, a great pianist or violinist does not think about individual notes, but hits them all perfectly in a virtuoso performance. In fact, thinking about a “C” while playing Beethoven’s 5th Symphony could be a real hitch because the flow might be lost.”

~Josh Waitzkin (8-time national chess champion and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu black belt)

What’s the point to all that? Well, this can make it very difficult for a well-seasoned maven to dig back down into the depths of their mind, in order to extricate, section out, and then teach the basal yet essential principles they learned long ago but now employ unconsciously.

It’s not that they can’t teach or mentor a student in the ways of their craft, but they may not be able to do so as well as others in the field. There’s a large difference knowing and teaching. For example, I’m sure many of you can recall a prior physics or math teacher, or sport instructor, who may have been brilliant within their craft but yet you had a difficult time learning while under their tutelage.

This concept even carries over to reading books. As I’ve sought to improve my chess game, I’ve actually found it quite helpful to not exclusively buy books written by Grandmasters (the highest achievable title in chess). You would think that a Grandmaster would be the best person to learn chess from, but, for reasons mentioned above, this isn’t always the case. For example, I have found treasure troves of insight within the works of Jeremy Silman, an International Master (one step below Grandmaster) who has built a strong reputation for his ability to teach beginners, despite the very fact that he is not a Grandmaster. It’s his knowledge of the game, in concert with his gift of teaching, that makes him shine, not the standalone fact that he’s a highly ranked chess player.

Ergo, when you seek mentorship from someone: they don’t have to be the absolute best; in fact, it may very well be optimal if they are not. You don’t need to head straight to the tip-top of the skill pyramid. Often you can find someone who is still extremely proficient (way more so than you), who will be able to instruct you and augment your learning process in a manner much more effective than even the “best” within that discipline.

Find a great teacher. Not necessarily the unparalleled expert.

2. Mentorship doesn’t have to be a formal, official arrangement

Probably one of the worst things you could do upon discovering a prospective mentor is to call them up and ask, “Hey, do you want to mentor me?” This is tantamount to you calling and saying, “Hey, do you want to take on an unpaid, part-time job?”

While I’d be remiss to assert that no successful mentorship has ever been started this way, this doesn’t change the fact that it’s still an odd way of asking. Even if they do say yes, it puts them in the awkward position of feeling like they need to plan out regimented meetings and send out a syllabus or something.

Here’s one of the most important things to know about mentors: a mentor is anyone you can learn from, who can impart wisdom upon you, who can directly or indirectly help to guide the decisions you make and actions you take. He or she can be a family member, a coworker, someone you already interact with quite regularly, or perhaps someone you only speak to on a quarterly basis. It also helps to ensure this individual is not a fool.

Some of my best and most fruitful experiences with mentors have risen out of informal relationships. From time to time, usually without it being planned in advance, they’ll provide me with a gem of seminal insight, or a particularly profound nugget of wisdom, which permanently alters my course for the better.

Should some mentorships be formal? Absolutely. But more often than not - at least during the beginning stages - it’s best to just let mentorship “happen.”

Don’t be the weirdo who comes right out and asks for it. That would be like my clumsy, ill-fated attempts to date a few women I fancied back in high school and college; rather than allowing our relationship to nurture and grow for a bit, and giving them subtle yet clear context clues of my interest, I just came straight out and asked, “Hey, would you like to be my girlfriend?”

Yeah, that rarely ended well.

3. Take a break and do something else together

Talk about things and do random crap that don’t at all pertain to your usual subject of study. Enjoy sarcastic banter and making fun of one another; grab a beer together; play a video game or chess; go on a bike ride; travel or go cliff jumping; play a sport; go see a movie or simply take a walk around town.

This accomplishes a couple things. First, it will help you connect to one another as human beings. It’s not rocket science: the more you get to know them, laugh together, and share a broad spectrum of experiences, the more you’ll be able to dismantle any personal barriers that you - often unintentionally - assemble and put up between you and other people. Within the context of mentorship, these personal barriers serve nothing other than to ultimately impede the learning process that could otherwise flourish unhindered between the two of you.

Second, and I can’t overstate this enough: it will nurture your creative processes in a profound way. Oddly enough, remaining singularly fixated on only the subject of study is not the optimal approach, even if your only goal is to learn that specific subject!

Steve Jobs knew this very fact, and summed it up well in an interview with Wired back in 1996:

“A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. They don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions, without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better designs we will have.”

~Steve Jobs

Broaden your experiences, not just as an individual but also with your mentor. It may seem like a waste of time, especially if you’re someone who becomes intensely obsessive with that one thing you’re trying to master or accomplish, but it will be more than worth it.

4. Remember they are not infallible beings

When you highly esteem someone, heavily admire their work, and love receiving advice from them, it can be easy to arrive at the subconscious conclusion that this person is without error or character flaws, to elevate them to something of a deity and hang on every word they speak or write as if it were inerrent ideology.

Then, when they inevitably crack (or shatter) the standard of perfection you’ve set for them - say, by making a mistake, or by slighting you in some way - it’s as if the ground crumbles beneath your very feet as the world comes crashing down around you. You either become pissed off at them and write off anything they ever said as fraudulent and worthless, or stew in despair and disbelief because the person who you believed would never mess up or upset you, just did.

Like anything in this world, when you make a good thing into an ultimate thing, it becomes an idol that will eventually enslave you, let you down, or both.

Nobody is perfect, and the privilege of being mentored by someone you highly respect is always an extremely delicate balance of trusting their wisdom and yet continually remembering they are nothing more than human; at the end of the day, they are prone to the very same pitfalls and character flaws as you. If they screw up, or irritate you in some way, just relax. Take a few deep breaths, forgive them, get over it, and get back on course.

5. Your personal network: don’t ignore the power of it, and don’t neglect to broaden it

While the maxim “it’s not what you know, but who you know” may be a cliche, that doesn’t make it untrue.

Everything from crucial internships, to the job I currently hold and love, to incredible opportunities I’ve experienced, to being connected with some crazy awesome and widely-respected mentors, have all been fruit I was able to pluck and enjoy as a result of seeds planted long ago in the form of interpersonal relationships.

This is one of the many reasons it’s imperative not only to refrain from burning bridges, but also to form as many as possible. You just never know how a friend, a prior coworker, or even an acquaintance, may be able to help connect you with a reputable individual who would otherwise be all but inaccessible. You can never have a network that is broad enough.

In fact - and I’m sure I speak for my fellow introverts when I say this - keeping in mind the above sentence is one of the primary tonics that keeps me going during formal social gatherings and conventions. You know, those dreaded events which require one to endure that insufferable affliction otherwise known as small talk. I would rather swallow a live hand grenade than spend a few hours small talking with strangers who I’ll probably never see again. But again, you really never know what may come as a result of it - they may be able to help you, or you may be able to assist them, in remarkable ways.

While by no means exhaustive, I hope the above points provide a small window of clarity into the often cloudy and undefined realm of mentorships.

Agree? Disagree? I’d be curious to hear anything you’ve found helpful, be it with the actual finding of mentors, or nurturing the relationship once it’s already formed.

Rate of Force Development: What It Is and Why You Should Care

No, sorry, this is not a post on how to become a Jedi by increasing your rate of using the Force. Shucks.

The Rate of Force Development (RFD) we're going to talk about is that of muscles and is *kinda* important (read: essential to athletic performance). Today's post will enlighten you as to what RFD is and why one should pay attention to it. Next post will be how to train to increase RFD. So grab something delightful to munch on (preferably something that enhances brain function, like berries.) Caveat: There is a lot of information and other stuff that I’m not putting into this post, sorry, this is just a basic overview of why RFD is important for everyone.

What is RFD?

It is a measurement of how quickly one can reach peak levels of force output. Or to put it another way, it’s the time it takes a muscle(s) to produce maximum amount of force.

For example, a successful shot put throw results when the shot putter can exert the most force, preferably maximal, upon the shot in order to launch it as far as humanly possible. She has a window of less than a second to produce that high force from when she initiates the push to when it's released from her hand. Therefore, it is imperative that the shot putter possess a high rate of force development.

Where does RFD come from?

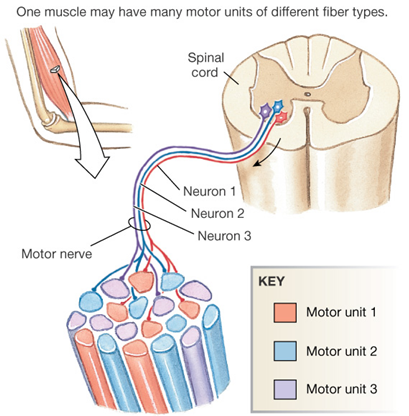

Well, let me introduce you to a little somethin’ called a motor unit. Motor units (MU) are a motor neuron (the nerve from your brain) and all the muscle fibers it enervates. It can be anywhere from a 1:10 (neuron:fiber) ratio for say eyeball muscles, which have to produce very fine, accurate movements. Or 1:100 ratio of say a quad muscle which produce large, global movements.

There are two main types of MUs: low threshold and high threshold. The low threshold units produce less force per stimulus than the high units. For example, a low unit would be found in the postural muscles as they are always “on” producing low levels of force to maintain posture. A high unit would be in the glutes, to produce enough force to swing a heavy bell or a baseball bat (even though the bat is light, the batter has to move that thing supa fast in order to smack a home run).

Also note the different stimuli required for the different units: small posture adjustments vs. a powerful hip movement. A low stimulus activates low threshold units and a high stimulus activates the high units.

Now, MUs are not exclusively low or high; MUs throughout the body are more like a ladder, low MUS at the bottom, with each successive rung being a higher threshold MU than the one below. And, like a ladder, you can just all of the sudden find yourself at the top of the ladder without having to climb the lower rungs. Unless of course, you’re a cat:

High MUs rarely (if ever) activate without the lower MUs activating first. So, the rate of force development is dependent upon how quickly the lower rungs of the MU ladder can be turned on to reach the highest threshold units (which produce the most force per contraction)… Not only that, but all those units working together produce more force than just the higher ones by themselves, so it's a good thing that the lower ones must activate too. The muscular force produced is the sum of all the motor units.

Why Care About RFD?

Since those higher threshold units won’t be active until the lower ones are on, force production will remain low until the higher ones can get their rears in gear, therefore, going up the MU ladder faster will result in more force produced sooner in any sort of movement.

Let’s take the example of two lifters, A and B. Both are capable of producing enough force to deadlift 400lbs. However, lifter A has a higher RFD than lifter B. Lifter A can produce enough force to get the bar off the ground in about 2 seconds and lock out (complete the lift) in about 3-4 seconds. Lifter B takes 3 seconds to get the bar off the floor and another 5 to get it near his knees. For those who don't know, a deadlift should be roughly 4-5 seconds TOTAL (typically, most people's muscles give out around then if the lift hasn't been completed). B-Man is going to fail the lift before he gets that bar to lock out and will hate deadlifting forever. Bummer.

Or, utilizing a Harry Potter for my analogy for this post, it is analogous to the rate of spell development; how quickly and how powerfully a wizard's spell is performed. In a duel, the faster and more forceful wizard will win. For example, when Professor Snape totally pwns Gilderoy Lockhart:

Hence, if one wants to get stronger, increasing the rate of force development is essential! Moving heavy weights is good (and high RFD helps with that as we saw with Lifters A and B from above); moving heavy weights FAST is even better when it comes to stimulating protein synthesis aka: muscle building. Possessing a high RFD is vital in order to move those bad boys quickly.

Next post, we’ll delve into training methods that can help increase the RFD so you won’t be these guys and skip deadlifting because your rate of force development is less than stellar…

Strength Training for Youths: Post-Puberty

Last post delved into training strategies for kids pre-puberty. Today we'll discuss weight training suggestions for kids after they've hit puberty. As I stated before, the American Pediatric Association states that puberty starts around 8-13 (girls) and 10-14 (boys). While a 10 year-old girl might be at the same sexual maturity as a 16 year-old girl, physically, mentally, and emotionally, they're vastly different. Therefore, I'm not going to train a 10 year-old the same as I do a 16 year-old.

So what's different?

To be perfectly honest: not much.The same principles of training youths apply across the age span.

1. Address and improve movement quality

2. Improve body awareness, muscular control, and coordination

3. Progressively overload (add weight or increase the difficulty of exercises) movements to produce positive adaptations appropriate to the athlete's physiological status. (Lotta big words for saying challenge the athlete to grow stronger in ways that will not hurt them.)

Coaches and trainers should always address movement above all. If the athlete moves like poop, adding weight is only going to ingrain the dysfunction that could, ultimately, lead to injury.

That being said, there are a few differences between the two age groups. Older athletes will, typically*, learn movements faster. They've been around longer, played more sports (hopefully), and have a fairly rich movement map. Thus, as they learn proper mechanics quickly, they can handle heavier loads sooner. Does this mean max effort? NO! (stop it, stop that nonsense right now!) It means they can SLOWLY add weights over the course of several months/years to their movements. Strength gains are a marathon, not a sprint.

Older athletes are ususally better at maintaining focus during their workouts (though not always...). This allows room for exercises that require more concentration. For example, an older teenager might front squat with a barbell-

-whereas a younger athlete will squat with a light kettlebell. The barbell squat requires (strength, duh) a greater amount of focus as the athlete has to remain tight to stabilize the bar as well as move in a correct squat pattern. Does this mean a 16 year-old moves straight to the barbell? Nope! They have to prove that a) they have the ability to move in a safe squat pattern (hips back, chest up, knees out) and b) they have the strength (core, upper back, legs). At SAPT we will NOT progress an athlete beyond what we think they're capable of just for the sake of using a barbell.

Older athletes can generally handle more complex movements. For example, a heiden to a med ball throw:

Versus our younger athletes who will work on those two movements independently (jumping and landing, and throwing a ball correctly).

Again, and I can't say this enough, progression should be tailored to the athlete's skill and ability. Throwing a barbell on the back of a teenager just because he's 17 doesn't mean he's able or ready to squat with that barbell. Being 17 does mean that, if he's demonstrated good movement and strength, we can probably progress him to the barbell (we wouldn't do that for a younger kid. They would just continue with kettlebell variations until they've grown a bit more).

The basic principles of training youths across the age-range are the same:

1. Address and improve movement quality

2. Improve body awareness, muscular control, and coordination

3. Progressively overload (add weight or increase the difficulty of exercises) movements to produce positive adaptations appropriate to the athlete's physiological status.

Older athletes will generally be able to:

1. Learn and load movements more quickly than younger athletes

2. Perform exercises that require more concentration

3. Perform more complex exercises

Overall, training youths is like vanilla ice cream: same flavor, different sprinkles.

*I say "typically" because we've seen older kids who have such poor motor control that we have to start them out as we would a 9 year-old and progress them accordingly. What a child does during their infant and toddler years matters! (oooo, teaser for next week!)

Strength Training For Referees: The Other Side of Athletics

Lift. Heavy. Things. That's a shocker, right?

But seriously, strength training regularly is exactly what refs and umpires need to stay in tip-top shape and last through the last second of the game. Weak referees tire, fall behind, and are not a metaphoric coursing river.

The physical demands of referees, at least the ones who run around with the athletes, do not deviate much from what is required of the athletes themselves. And those judges/refs who don'trun around, you should still lift heavy things as a general rule for conquering life. The basis of all movements (including standing during a whole match) is strength. Does your back get achey towards the end of the match? Prevention lies in the iron:

Granted, as the one observing the game, instead of playing, skill practice is not necessary. Being strong is. Can I say that enough in this post? Being strong is a necessary component to all aspects of athletics (and, really, life).Thus, weight training is vital to maintaining a healthy referee.

The beauty of strength training is that it doesn't have to be complicated; consider too that since you're not on a rigorous sport schedule (i.e. practices), your training can be rather minimal while still providing the stimulus needed to gain strength.

Let's say you have 2 days a week to strength train. What do you do? I recommend a full body workout on each day. Dan John presented a framework for training programs. I love it; it’s simple, quick and easy to remember.

Hip hinge (deadlift variation, glute bridge variation or swings)

Squat variation (goblet, barbell, bodyweight)

A Pull (such as a horizontal row variation or a pull/chin up)

A Press (i.e. push-up, bench press, overhead press etc)

Loaded Carry (Farmer Walk variation)

That will hit just about everything and you needn't spend hours in the gym. Hit a total of 25-30 reps of the main movement of the day (such as a 5x5, 5x6, or 4x8 set/rep scheme) and around that same total for the other assistance work. This allow for enough volume to actually have an effect and not too much so that you're overloaded.

Or, if you have 3 days at your disposal, you might want to do a lower, upper, and total body day. Keep the total number of exercises between 4 and 6, with the same 25-30 rep goals.

On the more shallow side, out-of-shape referees tend to draw criticism and heckling. No one wants that.

I know this is a brief post, but it's very simple and I don't want to overcomplicate things. And, frankly, if you're a referee, umpire, or judge, you were probably an athlete yourself and you understand the importance of maintaining strength; I don't want to belabor the the point and insult your intelligence.

Pick up heavy things. Swing Big Bells. And do Chin Ups.

Conditioning Strategies for Field Refs (Including Basketball and Hockey Refs)

If you're a referee for any of the field sports (football, soccer, rugby, field hockey, lacrosse, basketball, and ice hockey.. etc) you're well aware that there is a fair amount of jogging, sprinting, backpedalling, and dodging players throughout the course of a game/match.

Here's some fun facts for you:

1. Elite level soccer refs, head and assistants, run on the average roughly 10km and 7km, respectively per match. Not only that, but of that total distance, roughly 2km and 1km (respectively) is sprinting. That's a lot of sprinting!

2. In that same study of soccer refs, researchers found that main refs work at about 85% of max heart rate and assistants work in the 77% range. Again, that's a pretty high demand on the cardiovascular system.

3. High level rugby referees were found to have a 2:1 work to rest ratio of sprints to jogs/stationary, for a full 90 match. That is NOT a lot of rest between plays!

I imagine that from those studies we can extrapolate physical demands would be similar for football, lacrosse, and field hockey, and ice hockey. I would even venture so far as to say that the metabolic demands of a high-level basketball ref would be close, despite having less distance to travel from one goal to another. To quote the official Hockey Officiating Handbook:

A good official needs to be in excellent physical condition. Whereas players may skate a one-minute shift and then rest for a couple of minutes, the official is called upon to skate the entire game. An official deemed to be overweight and not in shape will have a difficult time keeping up with the play and will oftentimes be out of position.

Granted, the aforementioned stats were found in elite level referees, and I imagine the physical demands diminish proportionally to the level of sport (elite, college, high school and so on.) HOwever, the quote from the hockey handbook, I think, applies for any sporting referee. Think about it: the players are typically younger, have more time to train/recover (they may not have a second job, demands of raising/supporting a family etc.), and they have the goal of winning (which could, especially in a close game, overrule any fatigue).

I would also argue that the ability to maintain a high output throughout the game, especially towards then end when the points becomes more crucial, is essential to being a successful referee.

So, with all this information, what is the most efficient way to train? Here's how I would break it down:

Off-Season:

2-3 days of pure strength training

2 days of conditioning

In-Season:

2 days of pure strength

1-2 days of conditioning (the second day really should be more of a "bonus" day, if a game gets cancelled or something)

Since today's post is about the conditioning aspect, we'll focus on that (the strength portions will be later on). However, I DO want to point out that the strength training does NOT diminish during the season. Strength is the basis of all athleticism, including being a referee. The conditioning sessions drop in-season as actually reffing games will maintain aerobic conditioning.

Once again, that is if you're a consistent reader of this blog, I'm going to direct you to the Energy Systems post I wrote a while back. Why? Because it's important to understand, that's why. Most referees will have the same metabolic demands as a power athlete, that is, they'll be required to have intermittent high-intensity sprints with periods of jogging and/or complete rest. If you don't understand that having a solid aerobic base and how to build it efficiently, you can do all the sprint-repeats you want, but you're not going to get much better at recovering between those sprints without a

Energy Systems (READ ME)

Here are some great options for building the aerobic base:

High Intensity Continuous Training (explained here and here)- This is a great option as the impact is pretty low, so cranky joints shouldn't complain.

Rectangle Runs- Sprint the length of a field (start at roughly 70% and work up to 85% -90% over the course of several sessions). Walk the end lines. 1 rep = sideline sprint + end line walk. Start off with 6-8 reps (depending on your current level of conditioning) and work up to 10-12 reps per session. During the first couple of sessions, make sure your heart rate gets back below 150 beats per minute. As you progress, you'll notice that your heart rate will drop sooner during the rest periods. This bit is important because a) it helps build the aerobic base via recovery and b) allows for full force production during the sprint, thus improving your strength.

If you're really snazzy, you can practice sprinting with your head facing the inside of the field, as you would during a game.

Shuttle Runs - These will help improve change-of-direction and acceleration. The possibilities are endless with the reps and distances and rest periods. Again, to help work on the aerobic base and improve sprint capacity, let your heart rate recover to under 150 bpm between shuttles. Working without full recovery will eke you into the glycolytic state during the sprints and, as we all know, glycolytic power poops out pretty quickly over the course of a lengthy training session/game.

Hill Sprints - Find a menacing hill. Run up. Walk down. Repeat anywhere from 8-15 times. It's a pretty simple one.

Circuit Training- Here's an alternative to actual running for those poopy-weather days. I wrote about it here.

Ok referees, there's now no excuse for NOT training your cardiovascular system to attain tip-top physical condition. Get movin'!