Intensity: Get Some.

This post is written by the legendary Steve Reed You know what's interesting? Let's pretend I'm writing a program for two people that are nearly identical in EVERY WAY. They are of the same gender, carry the same body fat %, have the exact same metabolic rate, same poundage of lean body mass, are of the same biological and chronological age, are equivalent in neural efficiency, possess the same number of high threshold motor units, etc., you get the idea.

The program I write for both of them could be a perfect blueprint for fat loss, mass building, athletic performance enhancement, you name it. Yet, one of them will walk away, sixteen weeks later, looking and moving like a completely different person, while the other will move and look the exact same as they did when they started.

How could this be?

Well, I said that the two people are nearly equivalent. They are the same in every way, except for one key element. This critical difference is in their mindset. Namely, the former follows the plan with INTENSITY. Focus. Passion. Conviction.

The latter, however, follows the plan with the enthusiasm of a gravedigger. There's no light in their eyes as they move the weights around, and it's as if they're performing a chore for their parents before they get to what they really want to do. As Tony Gentilcore put it, their approach to squatting and deadlifting resembles a butterfly kissing a rainbow.

I was thinking about this the other day as I was observing the eclectic training mentalities I see on a weekly basis at my local commercial gym, and even sometimes at SAPT with people who walk through our doors for the first time. Especially when it comes to the accessory work (i.e. the movements after the squat/bench/deadlift portion of the session), you tend to really see a drop-off in focus.

Sometimes, when I show something like a band pullthrough, glute bridge, or face pull, it's obvious the person doesn't care too much, and/or is worried what others may think:

"Man, this looks awkward" "This movement can't really be of any importance" "I wish he'd stop giving me this stupid exercise"

Let's take the band pullthrough and the face pull. This is what it may resemble:

If you go through the motions like this, how do you expect anything to happen?

Now, take Carson, one of our student-athletes. This kid gets down to business on everything. And I mean EVERYTHING. Bulldog hip mobility drills, walking knee hugs, broad jumps, band pullaparts, assistance work, and God help you if you get in his way while he's deadlifting.

I saw him training the other day and knew I had to film a few of his exercises. See the video below, and keep in mind he is not acting. This is how he actually lifts:

I mean, look at that face!!! He's thinking about NOTHING ELSE outside the immediate task at hand. He's snapping his hips HARD on those pullthroughs, and even during the sledge leveraging he's eying that hammer like he wants to kill it.

And, is it a surprise that Carson hit a 55lb deadlift personal record in a mere 12-week cycle with us?

Of course not. I wouldn't expect anything less with mindset like his.

It's time to train with some freakin' conviction and purpose when you enter the weight room. In fact, I'd even say become BARBARIC as you approach the iron. Even with your assistance work, take it on like you mean it. Then watch the results pour in.

Look, I do understand that many times there are external circumstances that may tempt to affect your mentality, both in and out of the weight room. And that not all of you feel very comfortable in the weight room, as it may be a fairly alien environment to you. Even if you're new to the gym and initially feel comfortable with just a few goblet squats and then getting on the treadmill, still attack it like you mean it! The faster you learn to "leave it all at the front door," the better off you'll be, and that's a promise.

The weight room has helped me through some of the most difficult times of my life. Sometimes it seems that iron seems like the only thing in the world that remains consistent to us. Two hundred pounds sitting there on the barbell is always going to be two hundred pounds.

So get in there and train like you mean it. Don't make me light some fire under those haunches!

How Low Should You Squat?

I was hanging out with some good friends of mine over the weekend, and one of them asked me about a hip issue he was experiencing while squatting. Apparently, there was a "clicking/rubbing sensation" in his inner groin while at the bottom of his squat. I asked him to show me when this occurred (i.e. at what point in his squat), and he demoed by showing me that it was when he reached a couple inches below parallel. Now, I did give him some thoughts/suggestions re: the rubbing sensation, but that isn"t the point of this post. However, the entire conversation got me thinking about the whole debate of whether or not one should squat below parallel (for the record, "parallel," in this case means that the top of your thigh at the HIP crease is below parallel) and that"s what I"d like to briefly touch on.

Should you squat below parallel? The answer is: It depends. (Surprising, huh?)

The cliff notes version is that yes in a perfect world everyone would be back squatting "to depth," but the fact of the matter is that not everyone is ready to safely do this yet. I feel that stopping the squat an inch or two shy of depth can be the difference between becoming stronger and becoming injured.

To perform a correct back squat, you need to have a lot of "stuff" working correctly. Just scratching the surface, you need adequate mobility at the glenohumeral joint, thoracic spine, hips, and ankles, along with possessing good glute function and a fair amount of stability throughout the entire trunk. Not to mention spending plenty of time grooving technique and ensuring you appropriately sequence the movement.

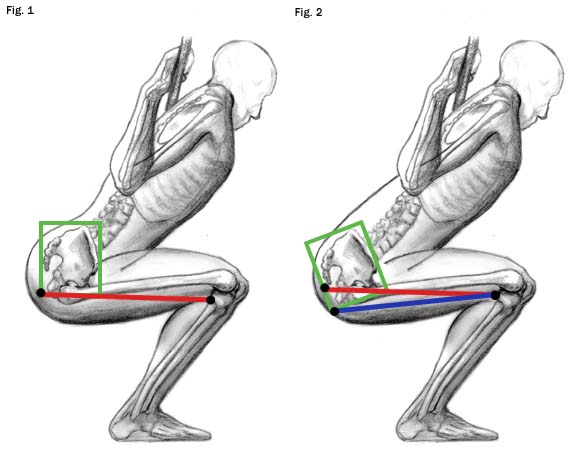

Many times, you"ll see someone make it almost to depth perfectly fine, but when they shove their butt down just two inches further you"ll notice their lumbar spine flex (round out), and/or their hips tuck under, otherwise known as the Hyena Butt which Chris recently discussed.

If you can"t squat quite to depth without something looking like crap, I honestly wouldn"t fret it. Take your squat to exactly parallel, or maybe even slightly above, and you can potentially save yourself a crippling injury down the road. It amazes me how a difference of mere inches can pose a much greater threat to the integrity of one"s hips or lumbar spine. The risk to reward ratio is simply not worth it.

The cool thing is, you can still utilize plenty of single-leg work to train your legs (and muscles neglected from stopping a squat shy of depth) through a full ROM with a much decreased risk of injury. In the meantime, hammer your mobility, technique, and low back strength to eventually get below parallel if this is a goal of yours.

Not to mention, many people can front squat to depth safely because the change in bar placement automatically forces you to engage your entire trunk region and stabilize the body. You also don"t casino online have to worry about glenohumeral ROM which sometimes alone is enough to prevent someone from back squatting free of pain.

Also, please keep in mind that when I suggest you stop your squats shy of depth I"m not referring to performing some sort of max effort knee-break ankle mob and then gloating that you can squat 405. I implore you to avoid looking like this guy and actually calling it a squat:

(Side note: It"s funny as that kind of squat may actually pose a greater threat to the knee joint than a full range squat....there are numerous studies in current research showing that patellofemoral joint reaction force and stress may be INCREASED by stopping your squats at 1/4 or 1/2 of depth)

It should also be noted that my thoughts are primary directed at the athletes and general lifters in the crowd. If you are a powerlifter competing in a graded event, then you obviously need to train to below parallel as this is how you will be judged. It is your sport of choice and thus find it worth it to take the necessary risks of competition.

There"s no denying that the squat is a fundamental movement pattern and will help ANYONE in their goals, whether it is to lose body fat, rehab during physical therapy, become a better athlete, or increase one"s general ninja-like status.

Unfortunately, due to the current nature of our society (sitting for 8 hours a day and a more sedentary life style in general), not many people can safely back squat. At least not initially. If I were to go back in time 500 years I guarantee that I could have any given person back squatting safely in much less time that it takes the average person today.

Breaking Down the Split Squat ISO Hold

The split squat ISO hold is extremely versatile, no matter if we're dealing with a new trainee, an advanced athlete, or someone looking to spice up their routine. It's the traditional split squat, but performed with an isometric (ISO) hold in the bottom of the movement. See the video below:

Why do I like it?

1. It's great for in-season athletes, or during a period leading up to competition. As a strength coach, it's critical to be able to provide the in-season athlete with a training effect, while simultaneously reducing the risk of muscle soreness. What athlete can optimally perform while he/she can hardly move his or her legs because they feel like jell-o?

The split squat ISO hold reduces the risk of soreness because it minimizes the eccentric portion of the lift, where the most muscle damage takes place (and thus contributes to that delayed-onset muscle soreness you typically feel 24-48 hours after a workout).

So, you can still receive a training effect (become stronger and improve neuromuscular control) while simultaneously reducing the soreness commonly felt after a lift. Sounds like a no brainer to me!

2. It's a great teaching tool for beginners. Many people nearly topple over (and sometimes actually do) when first learning the split squat. This shouldn't come as a surprise, as it's always going to require sound motor control when you move the base of support from two feet (as in the traditional squat) to one foot.

For the average person entering SAPT, I'll use the split squat isometric hold to help them learn the position. Depending on the person, I may have them start on the ground (in the bottom position), and then just elevate a couple inches off the ground and hold. This way, they're not constantly having to move through the full range of motion, where the most strength and neural control is required.

3. Like most single-leg variations, it trains the body to work as one flawless unit. As noted in the Resistance Training for Runners series I wrote earlier this year, lunge variations teach the body to work as a unit, as opposed to segmented parts. Specifically: the trunk stabilizers, glutes, hamstrings, quads, TFL (tensor fascia latae), adductors, and QL (quadratus lomborum) will all have to work synergistically to efficiently execute the movement.

4. To use as a change of pace. Yup...

Key Coaching Cues

- Get in a wide stance with the feet parallel to each other (as you'll see when I face the camera).

- Lower straight down. What we're looking for here a vertical shin angle (shin perpendicular to the floor). It's very easy to let the knee drift forward if you're not paying attention.

- Keep a rigid torso (upright). Imagine as if you're struttin' your stuff at the beach.

- Don't let the front knee drift inward (valgus stress). Keep the knee right in line with the middle-to-outside toes. I even cue "knee out" sometimes as many people really let the knee collapse inward.

- Squeeze the front glute to help keep you stable. You can also squeeze the back glute to receive a nice stretch in the hip flexor of the back leg.

- Perform for 1-3 reps (per side) with a :5-:15 hold in the bottom.

A good way to improve your deadlift lockout…tear your calluses…and old skool video footage to prove it!!!

Today, from the vault I share with you deadlifting against bands. Staring myself, and two of my old training partners, with musical contributions by the great Earl Simmons aka DMX, the most prominent members of all the Ruff Ryders.

Applications for, and what I like about, pulling against bands:

-Great for improving lockout, or “crushing the walnut” as we say at SAPT. In retrospect, I’d program these in more of a speed, or dynamic, fashion as opposed to max effort (as seen in the video). I feel training the speed in which the hip extension occurs will ultimately have a greater carryover.

-You can really overload lockout without having to perform the movement in a shortened ROM (i.e. rack pull). Additionally, the overload at the top absolutely slams your grip, and promotes the adaptations necessary to handle your 9th max effort attempt of the day (in the case of a powerlifting competition which we were training for at the time).

-They are a great way to rip the calluses right-off your hand! You’ll notice at the 1:12 mark I do a dainty little skip at the end of my set; ya, that’s where I partially tear the callus, and then at the 1:45 mark is where I finish it off. Great, thanks for sharing, Chris.

***Note, a great way to keep your calluses at bay is while in the shower gently shave over them with your standard razor. This removes most of the dead skin while not removing the callus all together. Thanks, Todd Hamer!***

What I don’t like about pulling against bands:

-Kind-of a pain to set-up.

-They put the bar in a fixed plane which may be detrimental for some trying to find their groove.

-From a programming standpoint I feel that they are more of an advanced progression and therefore aren't appliciable to most.

-They’ll rip the calluses right-off your hand!

Yes, it should be noted that the lifting form exhibited in the video, by one individual in particular (crappy, fragmented footage used to protect the innocent), should not be used as reference for a “how to” deadlift manual. Might I suggest you focus on the swarthy young-man in the green t-shirt…

Good times…hard to believe it’s been three years…

Chris AKA Romo

Cluster Training: Your Meathead Tip of the Day

Note - This is a re-post from about a year ago:

Cluster Training is a form of interval training in which, much like track athletes, the goal is to increase strength-endurance by manipulating and cycling work and recovery phases. Clusters, specifically, involve performing one or more repetitions with 10-20 seconds rest between each repetition or “cluster” of repetitions, in the case of an extended set.

Notes for cluster success:

Minimum load used is a 5RM for 4-6 sets

Extensive clustering – 4-6 repetitions with 4-6RM and a 10 second rest between each cluster.

Intensive clustering – 4-6 sets with 75-90% 1RM with 20 seconds rest between online casino repetitions for 4-6 repetitions total. Ex: 6x1x4 @ 80-85%

Clusters are best used in moderation during times when a plateau needs to be smashed to continue forward progress. I would suggest only applying this method once a week for a two- or three-week wave.

Trimming the Fat: Some of My Fastest Gains Ever

Every now and then I like to peruse my old training logs, peeking back in time to take a glimpse at what I was doing in the weight room; be it three months ago or three years ago. The other day I decided to flip through my logbook from college, and was suddenly reminded of the sudden, and dramatic, shift my training took at one point. You could call this my "Enlightenment," or, when I discovered that it was possible to accomplish more in less time. You see, for the first few years of college, I was following a classic bodybuilding split, utilizing tips I had picked up from the muscle mags and various personal trainers that crossed my path. I would work 1-2 body parts a day, training six days per week on the average. Each of these training sessions lasted about 90-120+ minutes, and I would utilize about 4-5 exercises per muscle group, performing 4-5 sets for each exercise. I'd incorporate just about every exercise I could think of, "attacking my muscles from all different angles" just like the magazines told me I needed to do. I was doing pretty well for myself, too: adding some muscle here, getting stronger there, maybe getting a new vein in my arm. *high five!*

After all, the more I could squeeze in, the better, right?

However, toward the end of junior year, I decided it was time to seriously investigate my training. This meant looking beyond the magazines in the grocery aisles, and seeing past what the majority of gym-goers were doing. To make a long story short, this is when I discovered some extremely valuable information and began reading from authors/strength coaches who actually knew their stuff. The strength coach for Virginia Tech was also extremely accommodating and patient with me, answering the endless slew of questions I incessantly threw at him as I first began to shadow his work with the athletic teams.

I suddenly realized that I didn't actually need to train 12 hours per week to become bigger or stronger. It was far from essential to do 25-30 exercises per week. It wasn't necessary to spend an entire day on one body part. And it wasn't required to perform countless drop sets and supersets of isolated delt, bicep, and tricep work to make my shoulders and arms grow. In fact, it turned out that a mere 20% of my efforts was responsible for 80% of my results. I became educated on the minimum effective dose, or, the minimal stimulus required to produce a desired outcome.

It was time to "trim the fat," so to speak, with my training. I wanted to test this for myself, to see if it was REALLY true. I mean, it's one thing to read about it, hear others talk about it, but it's a completely different bear to induce change upon YOURSELF, especially when there's a young ego at stake.

As such, I made up my mind to undergo a plan that would have me training no more than four days per week, and my sessions would be required to take no longer than an hour (excluding warm-up). Inspired by Alwyn Cosgrove, I decided to choose only two different workouts, and I would alternate between the two every time I set foot in the gym. I had a "Workout A" which was essentially lower body emphasis, and a "Workout B" which was upper body dominant. Here it is below:

Workout A (Lower Body)

Workout B (Upper Body)

A) Squat B) Deadlift C1) Bulgarian SplitSquat C2) Barbell Step-Up

A1) Incline DB Press A2) Seated Cable Row B1) DB Military Press B2) Pullup C1) Close-Grip Bench C2) Ab something

That was it. For six weeks, that is all I did.I would typically perform Workout A on Mondays and Thursdays, and Workout B on Tuesdays and Fridays. A method of undulating periodization was applied for the sets and reps each day.

And what do you know? My arms, shoulders, chest, and legs all continued to grow, despite the fact that I was I was training only four hours per week. This was one-third of the time I was spending in the gym all throughout high school and the first half of college. I had more free time, the workouts were surprisingly brutal (especially on the high rep squat days), I didn't constantly feel sore, and I was receiving an increasing number of the "So, what have YOUbeen doing?" or "What supplements have you been taking?" (<== lol) questions.

Now, there's no doubt that some of my gains can be attributed to the fact that I dialed in my nutrition further, and was actually deadlifting for the first time (in fact, I'd go so far as to say that deadlifting alone attributed to the majority of my gains). Also, one will almost always experience progress in one form or another when switching up the routine. However, there was no doubt that something was working.

In fact, things were working so well that I decided to enter a new eight-week cycle:

Workout A (Horizontal Push/Pull)

Workout B (Lower Body)

Workout C (Vertical Push/Pull)

A1) Bench Press A2) Bent-Over BB Row B1) Incline DB Press, Neutral Grip B2) Seated Cable Row

A) Snatch-Grip Deadlift B1) BB Forward Lunge B2) BB Step-Up C) Ab something

A1) BB Overhead Press A2) Pullup/Chinup B1) DB Arnold Press B2) Lat Pulldown

And the gains continued to come. I was stronger and leaner, I felt better, and, yet again, was accomplishing this in far less time that I had for the years prior.

An Important Note Were these "perfect" programs? Not at all. (Is there a such thing anyway??). In fact, looking back, there are quite a few obvious tweaks I would make. HOWEVER, at the time, I was trying my best to apply the principles I had learned in my research. And that's the important part.

Summing all this up, here are the take home points:

- Less is more. You can nearly always accomplish the same, if not more, by trimming the fat in a training program. Water boiled at 100ºC is boiled. Higher temperatures just consume more resources that could be used for something else more productive.

- While the high volume bodypart split routines can work for the genetically elite, they often aren't the best choice for the majority of trainees (and, as a side note, certainly not athletes).

- You don't need 6+ hours a week to get stronger, lose fat, or put some lean body mass on your frame.

- When in doubt, choose exercises that are multi-joint over single-joint.

- Deadlifts are awesome.