Parent's Field Guide to Spotting Trouble (and possible injury)

Injury in youth sports continue to climb. Coach Sarah Walls shares tips on how to identify possible trouble before it becomes a major injury in her Parent’s Field Guide to Spotting Trouble.

As a parent, my number one job at all times is to make sure my children are safe. Period.

When they’re young, what we’re looking for as parents is a piece of cake: things like shouting “Look both ways!” as they get ready to cross the street. Or, “have you washed your hands?” before dinner. But, as our children turn into young adults with their physical abilities developing at lightning speed, it can become less obvious to know what to do, say, or ask when you sense *something’s* not right.

At the youth levels (under age 15, especially), coaches are almost always under supported, so waiting on the coach or a member of the medical staff (ha, the team doesn’t have that - you’re it!) to make the call or assessment is likely inefficient.

Get Certified!

Before I dive into my tips, please be sure to take the time to take and/or maintain a current CPR/First Aid course. This is a crucial step helping to identify and respond to emergencies. Having as many people around sporting competitions who are trained in these areas is extremely important and falls under the “it takes a village” category.

Let’s Get to It

Alright, to help with spotting signs of trouble early, below is a field guide of sorts based on the information I’ve gathered over the years. Injury and potential for injury is something that I’ve spent countless hours and many years cataloging as I watched thousands of practices and competitions.

Here’s the thing I want to get across: I’ve learned to greatly appreciate how important it is to put the health of the athlete’s body over all else. As a parent, I’m sure you agree and want you to know that you can and should help.

You may read some of my below recommendations and think: there’s no way my kid is going to get taken out of practice simply because of X, Y, or Z. But, if the consequence of NOT taking action is life altering pain or surgery, would it be worth it?

Here are five things to look out for:

Trust your gut. No one knows how your child moves, feels, and responds to questions better than you. If something feels off, you should investigate further.

Discuss the realities of injury with your child at a time outside of practice/competition. Explain that your main goal is to keep them safe/healthy and if you notice something you want to know more about that you may pull them aside to find out more. Setting expectations ahead of time can go a long way “in the moment” when they don’t want to answer your questions.

Watch locomotor patterns: this is a big one! If your child’s gait becomes visibly abnormal and doesn’t smooth back out after a few minutes, you will need to find out what’s going on. A stride with a visible limp or another compensatory pattern of some kind (leaning to one side, for example) must be addressed.

Possible causes to consider: previous injury, strained muscle(s), stress fracture, growth, stress reaction

If your child is coming back from muscle strain or another known injury, just a brief check in to find out how they’re doing and then reverting to the action plan, as needed

If there is no known injury, ask questions and use your best judgement.

If your child is able to normalize their gait within a few minutes, make a mental note and follow-up afterwards.

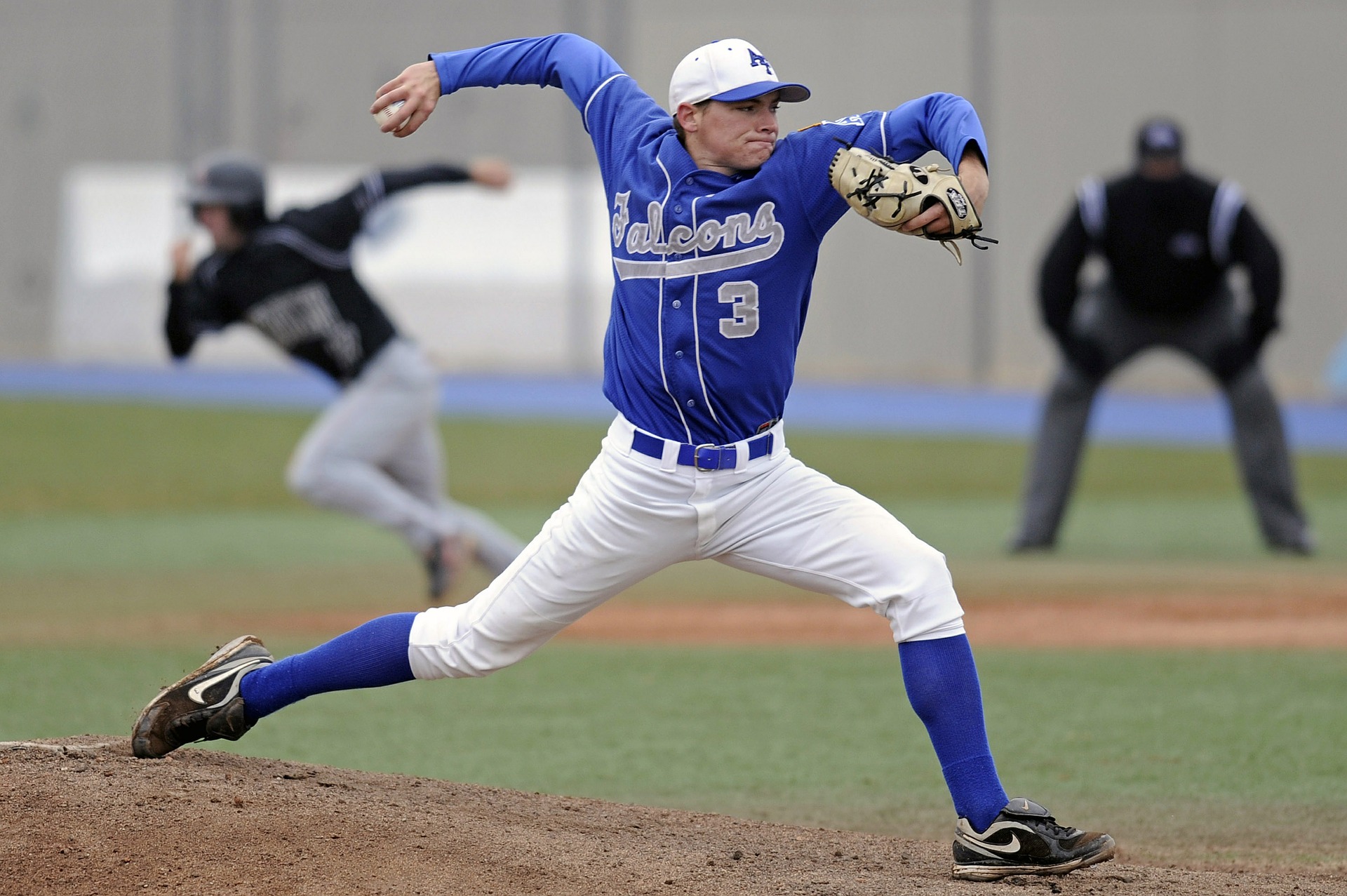

Repeatedly grabbing a body part after movement: you usually see athletes do this who are working through some kind of discomfort (ex, pitchers and their shoulders or elbows). Use this as a trigger to ask questions.

It is worthwhile to find out where the discomfort is coming from: joint, muscle, or something internal? As this will give you insight on any subsequent actions that need to be taken.

Young athletes will often give a response indicating they’re “working it out” or “a little tight”. From experience, I can tell you that something at least slightly more significant is underlying those answers. Root causes often harken back to a strength deficit and/or overuse.

Head impact: this could be a fall to the ground or an impact with another player or object. Head injury should be taken very seriously and always err on the side of caution. If your child was knocked unconscious, seems disoriented, or vomits as a result they need to be removed from practice/competition and evaluated by medical personnel.

A couple other tips to help your kids succeed: keep an eye on hydration (all sports) and temperature (outdoor sports) - climate change is real and exposure to extended periods of extreme heat should be considered and planned for; check out the warm-up - a thorough warm-up is important to reduce injury; have the proper equipment - you don’t have to buy the most expensive options, just be sure shoes, clothing, gloves, etc fit well.

This is a light list of what to watch out for, but in my experience these cover the majority of trouble areas for most sporting activities. If you are a parent reading this, I hope that you feel encouraged and supported to raise the red flag when things are off. Just remember to trust your gut and ask questions.

Since you’re here: We have a small favor to ask! At SAPT, we are committed to sharing quality information that is both entertaining and compelling to help build better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage us authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics.

Thank you! SAPT

Smart Circuit Training

Circuit training is the method of endless possibilities! Coach Sarah Walls shares a workout that checks all the boxes you want in an effective circuit: challenge, variety, effectiveness, and intelligent planning.

An athlete’s ability to repeatedly produce high amounts of power - and then recovery quickly to do it again (and again… and again…) is the definition of fitness for team sports.

Lately I’ve been working with an athlete rehabbing from a lower body injury who needs to keep her cardiovascular conditioning and fitness as high as possible. It’s been a great challenge and has gotten me utilizing some methods and equipment I don’t regularly utilize.

Circuit training, in particular, has been crucial.

It’s really important to keep training, even with an injury, you just have to be smart about it. Otherwise, the athlete will come back from injury only to find themselves woefully out of shape - which can lead to a new injury simply from fatigue when they try to pick up their sport again.

There are truly unlimited possibilities when it comes to circuit training. A basic understanding of what you want to get out of the session should help guide some decent decision making. Always be sure to factor in some rest time and/or active recovery.

I’m also a big supporter of self-regulation. If your body says it needs to go slower or rest, then give it what it needs! We always want to train with the intent to “live to fight another day”. There will be another workout to push to your limit.

Here is a circuit that I designed for myself that focused on repeated efforts of maximum power with active recovery. All active recovery exercises were chosen for my specific injury prevention needs:

Explosive Belt Squat x5

*Scap Pull-up x10

Explosive Lat Pulldown x5

*Heel Raise x10

MB Keg Toss x5

*Full cans/Empty cans x10

Explosive Push/Pull x2/way

*Elliptical x:60

Active recovery exercises indicated with the asterisk and italics.

I was able to monitor power output on a rep-by-rep basis throughout the session, but if you want to give this a try and do not have access to that type of feedback just simply do each of the main exercises with as much speed/force as you can generate for every single repetition.

Let me warn you: the above is not for the faint of heart. The repeated focus on power was a real difference maker. Be smart with the amount of total time you want to work. This session was done for 7 rounds and that took around 45-minutes. It was exhausting. Like impacts-the-rest-of-your-day exhausting. I suggest targeting 20-minutes or so for your first time.

Feel free to substitute your own exercises for the active recovery choices. If there’s a chink in your armour, this is the perfect opportunity to know your staying fit and pushing yourself with exercises that are safe for you, while also getting the extra reps on your prehab/rehab exercises.

Since you’re here: We have a small favor to ask! At SAPT, we are committed to sharing quality information that is both entertaining and compelling to help build better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage us authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics.

Thank you! SAPT

My Hip Hurts! Training with a Hip Labral Tear, Part 1

So your hip hurts? The good news is there are always safe workarounds in the case of injury or lingering issues. Coach Sarah Walls begins her two part series on understanding how to apply safe training to the lower body with a labral tear in the hip.

So your hip hurts? I’m sorry to hear that - mine does, too! The good news is there are always safe workarounds in the case of injury or lingering issues (that should be accounted for as they always add up to real injuries down the road).

If you’d like to learn about the “why” behind some hip trouble, check out: "My Hip Hurts!" Training Around Femoroacetabular Impingement

Today, we’re just going to start talking more specifically about solutions for hip impingement - often felt as a pinching or dull ache - and often resulting in hip labral damage (there is a wide variety here).

It’s a pretty good rule of thumb that squatting is either not recommended or recommended to be heavily modified for athletes who are having hip labrum issues. This is because of the high degree of hip flexion during the squat - or where the knees come closer to the chest - can cause some major problems in the hip. The usual recommendations to modify the squat are to adjust depth or move more towards unilateral exercises (like split squat and lunge variations).

Hip IR/ER: the body needs a balance of both and should be both strong and mobile throughout both rotations.

Some strength coaches have famously denounced the bilateral squat pattern because they feel the risk vs reward does not make sense and will remove the movement all together.

I’m not there, yet! But I will say, that for the athletes I work with, they almost all have the same risk factors in common: poor ankle ROM, long femurs, and short torsos (relative to leg length). This is a recipe for hip trouble over the long term.

In these cases, I like making unilateral lower body exercises the main lift (be it as a precaution or a necessity) because it ensures we are getting a full range of motion in training the legs. Then we don’t have to rely so heavily on squatting to full-depth to get proper training effect.

The classic box squat. Easy on the knees, great way to load the hips. Might this be too much of a “good thing” over many years with little variety?

But, adjusting squat depth and favoring lower body unilateral work is certainly not a new approach.

Here’s what is: combining postural breathing exercises while encouraging the natural internal rotation of the hip. I’ve been diving in deep on using postural breathing exercises coupled with hip adduction. These positional breathing drills, which are realigning the diaphragm and the pelvis simultaneously, while also involving the adductors and even the hamstrings. The adductors themselves do not get a lot of work while squatting, and could cause an imbalance or injury if not addressed (side note: a split squat DOES heavily involve the adductors).

Pounding the adductors, hamstrings, with a simultaneous “tail tuck” and “rib tuck” through exercises relieves the hip a bit in how we then start to train the surrounding musculature. This can be quite refreshing for the athlete over time. More on these specifics next week in part 2.

But why keep chasing the squat? Why bother trying to make adjustments? Why NOT just join the group that bans this movement pattern from lifts? 1. Variety is key (I’ll touch on that later); 2. A bilateral squat is VERY functional: defensive position, anyone? Bilateral jumping is also pretty darn commonplace 3. It allows you to use more weight and thus tax the core a lot more.

Not what I’m talking about! This is bad squat IR and shows weakness and lack of control. An injury waiting to happen.

Okay, I’ve convinced myself. Let’s keep plugging away:

Most coaches when coaching the squat do not allow for natural internal rotation of the hip, true, most coaches will coach athletes to drive the knees out really hard and maybe even use a wide stance as well.

The opposite of this, and perhaps the more natural way to squat, that I’ve been experimenting with lately is this idea of not driving into so much external rotation when squatting, and allowing a little bit of natural internal rotation.

With this knee travel, the knee must remain inside the toe box and we should see this slight motion in the deeper portion of the squat or as part of a natural motion in the split squat. Again, and I can’t emphasize this enough, the knee motion is very slight, always under control, and stays within the toe box.

If you are struggling with hip pinching or catching, I recommend getting the hip looked at by a qualified medical professional who can help you understand what’s going on inside. If things are looking manageable, that’s awesome! You can train.

Please come back next week for part 2 of this post and I will share exercises ideas, specific training days, along with safe loading parameters. Getting the correct work-arounds will help you not only feel better but also feel like you are making progress once again.

Since you’re here: We have a small favor to ask! At SAPT, we are committed to sharing quality information that is both entertaining and compelling to help build better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage us authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics.

Thank you! SAPT

Hidden Problem of Early Sport Specialization

Early sport specialization is not only about children getting injured too young because of only playing one sport. It is also about how this model removes the opportunity to teach children how to take care of themselves from a physical movement and strength perspective, by focusing solely on sporting success and mastery. Coach Sarah Walls discusses a broad approach to what can be done in this multi-part series.

Early sport specialization is not only about children getting injured too young because of only playing one sport (and, therefore, not reaching their potential as athletes - this is the club sport model), it is also about - and dare I say this is the more important, yet less discussed part - how the early sport specialization model removes the opportunity to teach children how to take care of themselves from a physical movement and strength perspective, by focusing solely on sporting success and mastery.

In our fanatical quest to produce the top athletes, we effectively are a country producing adults who do not know how to eat healthfully or keep their bodies strong. We set them adrift in adulthood to fend for themselves. Many only knowing to search out an adult league [soccer, basketball, volleyball, etc.]. High school sports were, for many, the last time they were “in good shape.” It is understandable how this would be what is naturally sought out.

Recently, I caught the end of a conversation between Ryan Wood, one of SAPT’s coaches, and one of our interns, Iman. They were talking about the problems with early specialization in sports and how that affects the general population over the long term.

What is early sport specialization? The more traditional definition: when a child younger than age 15 plays one sport year-round. My expanded definition: when children are taught from a young age via PE that physical health is found in competitive team and individual sports.

During this conversation, Ryan brought up a great point that I had never thought of before: All of the conversations surrounding early sport specialization generally consist of explaining why these athletes that are specializing in one sport at a young age are getting injured and how detrimental this is for developing athletes to their full potential. True.

But what Ryan pointed out was that this is a very short-sighted concern. You see, Ryan teaches physical education (PE) and is very focused on long-term human development. So he really gives a lot of thought to what we, as a society, are doing in PE and more specifically about what PE should be doing for us.

In my opinion, the concept of physical education is just the same as learning math skills or learning science skills. We should be learning how to take care of our physical bodies in a step-by-step process and then taking these skills with us into adulthood and using them over a lifetime.

Learning how to take care of our physical bodies (Physical Education) at a young age and progressing appropriately through high school could help us - again, as a society - dramatically reduce injuries and illnesses associated with inactivity and poor food choices. And, honestly, just produce happier adults.

As best I can recall, I’m not using anything that I learned from my 12-years of physical education. I remember learning to play dodgeball, kickball, ultimate frisbee, archery, dancing, volleyball, and basketball, but that was about it.

Teaching while modeling how to care for yourself physically should be the foundation of Physical Education programs.

For the most part, PE was the time to goof around while looking forward to my volleyball practice after school. Getting to shoot a compound bow for a couple weeks was pretty cool, but a life skill? Not quite.

I would have been far better served by being taught some strategies to help me stop spraining my ankle regularly and learning to become more mechanically sound in throwing a ball to lessen the painful tendonitis I developed in my elbow. Both of these issues prevented me from competing to my fullest, but in the long-run [read: even today] are both recurring issues that harken back to when I was 14 or so.

Everything in PE was and is at an introductory level. The skills being taught do not effectively build on each other. Think about it this way: how do we learn to read and write? It starts with simple things like learning the alphabet, learning sounds, and learning words. Over time, we gain varying levels of mastery of the language(s) we’ve focused on learning. The skills build on each other.

We can generally say that physical education is not currently working the same way as other subjects are taught - and it should be! Children are learning a rotation of specialized sports skills. Not the knowledge they need to take care of their physical bodies.

Please check out Part 2 of this blog: How America’s PE approach normalized the inefficient and dangerous youth sports development model at the club level.

Since you’re here: We have a small favor to ask! At SAPT, we are committed to sharing quality information that is both entertaining and compelling to help build better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage us authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics.

Thank you! SAPT

Performance Nutrition: Collagen Supplementation

Collagen protein has emerged as a way to speed up recovery from injury - and almost any injury at that! But is it just another carefully packaged, expensive product with little to show in the way of research supporting its use? Or does it work as advertised? Coach Sarah Walls explores the research and shares her experience in using a specific protocol.

Okay, so I am not claiming to be a collagen expert, but there is some interesting information I want to share as I think it can help many, many people.

Over the last couple of years, collagen protein has emerged as the next darling of supplements in the multi-billion dollar fitness industry. It is touted as a way to speed up recovery from injury - and almost any injury at that!

But is it just another carefully packaged, expensive product with little to show in the way of research supporting its use? Or does it work as advertised?

Let’s find out more.

What is collagen exactly?

“Collagen is the most abundant protein in the body and helps give structure to our hair, skin, nails, bones, ligaments and tendons in our body. Thanks to collagen, we’re better able to move, bend and stretch. Collagen is also behind helping hair shine, skin glow and nails stay strong.” - Vital Proteins website

What does collagen supplementation do?

The product makers claim that making an effort to consume collagen protein can help do everything from restore the bounce in your skin to shine in your hair and even help bones, ligaments, tendons, and muscles repair after injury.

Wow, that all sounds awesome! Count me in! Well, wait… let’s explore the last part of those claims a bit by focusing on injury.

Does collagen supplementation really help?

If you check out these two studies (here and here) it is pretty clear there is evidence that supports its use in acute injury.

That’s really great news. But what you pair the collagen with, plus when you take it, prove equally important.

Here is a bit of structure on how to use during the pre-workout timeframe:

Step 1: First and foremost, in the realm of recovery from injury, gelatin works just as well as collagen. So, if you are on a budget, making some old fashioned Jello may be just as good, if not better. Secondly, and most importantly, pair the collagen/gelatin with Vitamin C. The dietician I work with recommends 50mg.

Step 2: Consume about one hour before exercise. The idea here is that the collagen will get synthesized into the various structures of the body at an increased rate when taken before exercise and especially when paired with Vitamin C.

Step 3: Have a training session, practice, or rehab session that is loading/stressing the recovering area.

Step 4: New information is surfacing about multiple “doses” per day being especially effective. So, you could consider having a second serving later in the day (not necessarily paired with exercise).

Step 5: Give it some time. How much? I’m not sure, but probably 2-weeks at minimum to see if you notice improvement.

I’ve been using this protocol with some of the athletes I work with and we’ve had very encouraging results. So, I’d say it’s worth a try.

Taking this a bit further, I think there is reason to consider using collagen/gelatin in a pre-workout timeframe for anyone training who wants the best possible adaptation to the training/practice load. Meaning: even non-injured athletes could expect good results.

Part of the benefit to running, jumping, and resistance training is how dense and robust it makes the body’s tendons, ligaments, and bones. All those same benefits can seemingly be amplified by this little tweak to your pre-workout nutrition. Thus, potentially cutting your risk of injury.

Personally, I have a heck of a lot of trouble with my tendons, in particular. So, I’m going to give this protocol a month and see where we end up!

Since you’re here: We have a small favor to ask! At SAPT, we are committed to sharing quality information that is both entertaining and compelling to help build better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage us authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics.

Thank you! SAPT

Breathing Basics: Switching Sympathetic to Parasympathetic

Learn how to quickly switch into a focused, but relaxed state for your training session or practice, while optimizing air flow pathways.

Breathing drills have become an important foundation to each and everyone of my training sessions and it is something that, while complex on the surface, can be implemented in very simple ways that come with huge payoff.

If you want to get a primer in breathing drills, please check out my post from a few years back to get a foundational understanding of WHY they can be an important part of any training session: BREATHING DRILLS

In the past, I really only used one breathing drill per session, today it is up to a minimum of three. I like using a 3-drill circuit as the first thing the athlete does in their session for dual purpose of reaching the autonomic nervous system and targeting the respiratory muscles for warm-up purposes.

When using these drills in this way, paying attention to the way the athlete is breathing is very important. In this case the correct way would be to get as much air in as you can through your nose, hold it for a moment, and then exhale through the mouth.

Perhaps this runner could benefit from a pre-session breathing circuit to help optimize airflow and prevent excessive exhaustion?

Outside of this there are body positions that are more optimal to do this in than others, however this may be more useful when we are trying to reset positions than anything else. In truth, it really does not matter the position in which you are breathing, the most important thing is that we are breathing deeply.

The main goal of this type of breathing drill is to take us or our athletes from a sympathetic to a parasympathetic state. This would mean switching your brain away from the daily stresses that all people deal with (from their boss, family, relationships, etc.) to focusing on the practice/training session in which they are about to engage. It helps the mind separate from the noise that doesn't help while you’re training, practicing, or competing.

The other purpose that the breathing serves is to get the airflow to go through the body in a way that is extremely helpful for learning how to properly brace and support the spine. This is a safety enhancement, first and foremost, and a performance enhancement second. We want the body to be able to brace against and resist force, while we also want it to be able to produce force. Both of these are optimized with proper breathing.

Bracing and resisting against forces protects us from injury, while producing force is what aids our performance. Breathing drills are the easiest way to start to teach an athlete’s body how to do those things. The key is making sure that the airflow is going deep down into your belly and expanding into your lower back and into the sides of your waist.

With this style of breathing we are also activating all of the important muscles in the trunk that are involved in bracing. Activating these muscles help realign the bony structures in our body to aid in stability and bracing. For example, many people tend to have an anterior pelvic tilt. If you think about your hips as a bucket of water, if you dip it forward, that would be an anterior pelvic tilt, and the water is now spilling out a little bit. Breathing drills help us pull those hips back into neutral and teach the muscles what that feels like to be neutral and braced in that position. Another good example of this would be rib position.

Another common positional fault would be an overextended position in the ribs, which carries over to both injury risk and performance. This is another common postural fault that increases injury risk and can decrease performance just through an ineffective improper rib position. If someone is standing and they seem to be sticking their chest out, they are probably overextended. They're not just standing straight up, they're going beyond that. The telltale sign for this is we see the ribs sticking out. There are simple breathing drills that work to tuck those ribs back in and teach them where they should be. We need to get them to have a closer relationship with the diaphragm, which is extremely important from a positional standpoint.

Nothing fancy here. Just deep breaths.

We went pretty into the weeds here but the most important thing to take away is if you come into the gym a little stressed out, just take some time and do a breathing drill. For example, eight deep breaths as a minimum. You can do those seated, close your eyes or don't close them, just make sure that air goes in through your nose and out through your mouth, traveling deep deep down into your belly. Doing this alone will really help you feel more calm and ready to get into your training session or whatever it is that you're trying to transition into.

Since you’re here: We have a small favor to ask! At SAPT, we are committed to sharing quality information that is both entertaining and compelling to help build better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage us authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics.

Thank you! SAPT