Developing Strength & Power in Young Athletes: Youth Speed Training Workout #001

Coach Sarah Walls shares a developmental speed training session for children that is built around fun, coordination, strength, and speed.

For children who are physically and psychologically ready, this is a great single session example workout that provides lots of opportunities to work on coordination, strength, and speed training technique:

Overhead Stick March 2x15yd

Overhead A-Skip 2x15yd

Overhead A-Run 2x15yd

Front Rack Stick March 2x15yd

Front Rack A-Skip 2x15yd

Front Rack A-Run 2x15yd

PUPP Start 2-3x 15yd

3-Point Start 2-3x 15yd

2-Point Start 2-3x 15yd

Overhead Stick Squat 2x8

Hang Snatch with Stick 2x5

A1 BW Split Squat 3x5/leg

A2 Arm Mechanics from Seated Position 3x:10

B1 Suspension Strap Row 3x10

B2 Push-up Eccentrics 3x3

C1 Conventional Deadlift Technique 3x3

The marches, skips, and stick runs in the first portion are serving to provide a thorough warm-up. It would be totally appropriate to add in other ground based warm-up exercises beforehand, too.

Keep a close eye on children’s fatigue level throughout each set and always offer plenty of opportunities to take a break or get water. For kids not used to this type of work it can be very fatiguing and they may need time to build up their work capacity. We go through the whole session at a leisurely pace and have plenty of time for laughing, joking, and questions built in.

This entire session is predicated around working on technique and I am always ready with a regression or progression in case a certain exercise is not a good fit on any given day. For this particular session, my daughter has recently grown 3/4” and was struggling with the balance for the Split Squat. So, I quickly told her we’d adjust to using body weight (instead of 10lbs) and even gave her a bit of support/assistance by letting her hold onto my arm when needed. This approach got us the good technique I was after and helped to keep her feeling successful.

The development of strength and power in youth has previously been a source of great debate, yet despite earlier misconceptions there is now a wealth of evidence supporting the use of resistance training by both children and adolescents. Conceivably, if a child is ready to engage in sport activities, then he or she is ready to participate in resistance training. -High-Performance Training for Sports

To get all the above done in one session is the result of a slow process of building. Before using something so lengthy, please make sure the children you want to use this with are ready both physically and psychologically. They should have a good work capacity and be excited to embark on this type of technique training. If they are not ready in either area, work needs to be done to get both areas improved so they will have a better experience with this type of workout.

Since you’re here: We have a small favor to ask! At SAPT, we are committed to sharing quality information that is both entertaining and compelling to help build better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage us authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics.

Thank you! SAPT

Hidden Problem of Early Sport Specialization

Early sport specialization is not only about children getting injured too young because of only playing one sport. It is also about how this model removes the opportunity to teach children how to take care of themselves from a physical movement and strength perspective, by focusing solely on sporting success and mastery. Coach Sarah Walls discusses a broad approach to what can be done in this multi-part series.

Early sport specialization is not only about children getting injured too young because of only playing one sport (and, therefore, not reaching their potential as athletes - this is the club sport model), it is also about - and dare I say this is the more important, yet less discussed part - how the early sport specialization model removes the opportunity to teach children how to take care of themselves from a physical movement and strength perspective, by focusing solely on sporting success and mastery.

In our fanatical quest to produce the top athletes, we effectively are a country producing adults who do not know how to eat healthfully or keep their bodies strong. We set them adrift in adulthood to fend for themselves. Many only knowing to search out an adult league [soccer, basketball, volleyball, etc.]. High school sports were, for many, the last time they were “in good shape.” It is understandable how this would be what is naturally sought out.

Recently, I caught the end of a conversation between Ryan Wood, one of SAPT’s coaches, and one of our interns, Iman. They were talking about the problems with early specialization in sports and how that affects the general population over the long term.

What is early sport specialization? The more traditional definition: when a child younger than age 15 plays one sport year-round. My expanded definition: when children are taught from a young age via PE that physical health is found in competitive team and individual sports.

During this conversation, Ryan brought up a great point that I had never thought of before: All of the conversations surrounding early sport specialization generally consist of explaining why these athletes that are specializing in one sport at a young age are getting injured and how detrimental this is for developing athletes to their full potential. True.

But what Ryan pointed out was that this is a very short-sighted concern. You see, Ryan teaches physical education (PE) and is very focused on long-term human development. So he really gives a lot of thought to what we, as a society, are doing in PE and more specifically about what PE should be doing for us.

In my opinion, the concept of physical education is just the same as learning math skills or learning science skills. We should be learning how to take care of our physical bodies in a step-by-step process and then taking these skills with us into adulthood and using them over a lifetime.

Learning how to take care of our physical bodies (Physical Education) at a young age and progressing appropriately through high school could help us - again, as a society - dramatically reduce injuries and illnesses associated with inactivity and poor food choices. And, honestly, just produce happier adults.

As best I can recall, I’m not using anything that I learned from my 12-years of physical education. I remember learning to play dodgeball, kickball, ultimate frisbee, archery, dancing, volleyball, and basketball, but that was about it.

Teaching while modeling how to care for yourself physically should be the foundation of Physical Education programs.

For the most part, PE was the time to goof around while looking forward to my volleyball practice after school. Getting to shoot a compound bow for a couple weeks was pretty cool, but a life skill? Not quite.

I would have been far better served by being taught some strategies to help me stop spraining my ankle regularly and learning to become more mechanically sound in throwing a ball to lessen the painful tendonitis I developed in my elbow. Both of these issues prevented me from competing to my fullest, but in the long-run [read: even today] are both recurring issues that harken back to when I was 14 or so.

Everything in PE was and is at an introductory level. The skills being taught do not effectively build on each other. Think about it this way: how do we learn to read and write? It starts with simple things like learning the alphabet, learning sounds, and learning words. Over time, we gain varying levels of mastery of the language(s) we’ve focused on learning. The skills build on each other.

We can generally say that physical education is not currently working the same way as other subjects are taught - and it should be! Children are learning a rotation of specialized sports skills. Not the knowledge they need to take care of their physical bodies.

Please check out Part 2 of this blog: How America’s PE approach normalized the inefficient and dangerous youth sports development model at the club level.

Since you’re here: We have a small favor to ask! At SAPT, we are committed to sharing quality information that is both entertaining and compelling to help build better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage us authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics.

Thank you! SAPT

Strength Training for Youths: Pre-Puberty

Last week's post listed persuasive (I think so anyway) reasons why kids should enroll in a strength training program. In that post is also a definition of a smart, sound training program. If you can't remember, here's the refresher; it involves none of the max effort, grunting/screaming/shouting version that, unfortunately, is the stereotype of our industry. Parents: NOT ALL TRAINING PROGRAMS ARE CREATED EQUAL!!!

Matter of fact, if you find your 9 year-old doing the same workout as your 16 year-old, something is dreadfully amiss. This post and the next will shed light on the differences that you should see between age groups, broadly, pre-puberty and post-puberty. Now, one thing to keep in mind as you read, these are general guidelines that apply to most of the population. There will be some puberty-stricken kids that are not prepared to train like their peers (meaning, they will be regressed considerably) and there will be some young kiddos who's physical development far exceeds their peers (though it does NOT mean they're ready for large loads; instead they'll have more advanced bodyweight and tempo variations.).

Right, let's hop in.

According to the American Pediatric Association, puberty starts between 8-13 for girls, and 10-14 for boys. For today's discussion, let's assume 15 years is the game changer in physical development. In my experience, kids under 15 still are pretty goofy and often don't have the muscular development that a 15 or 16 year old will (boy or girl). Between 8-15 a LOT of growth happens (and beyond for most boys, but we'll ignore that for now). That segues nicely into my first point:

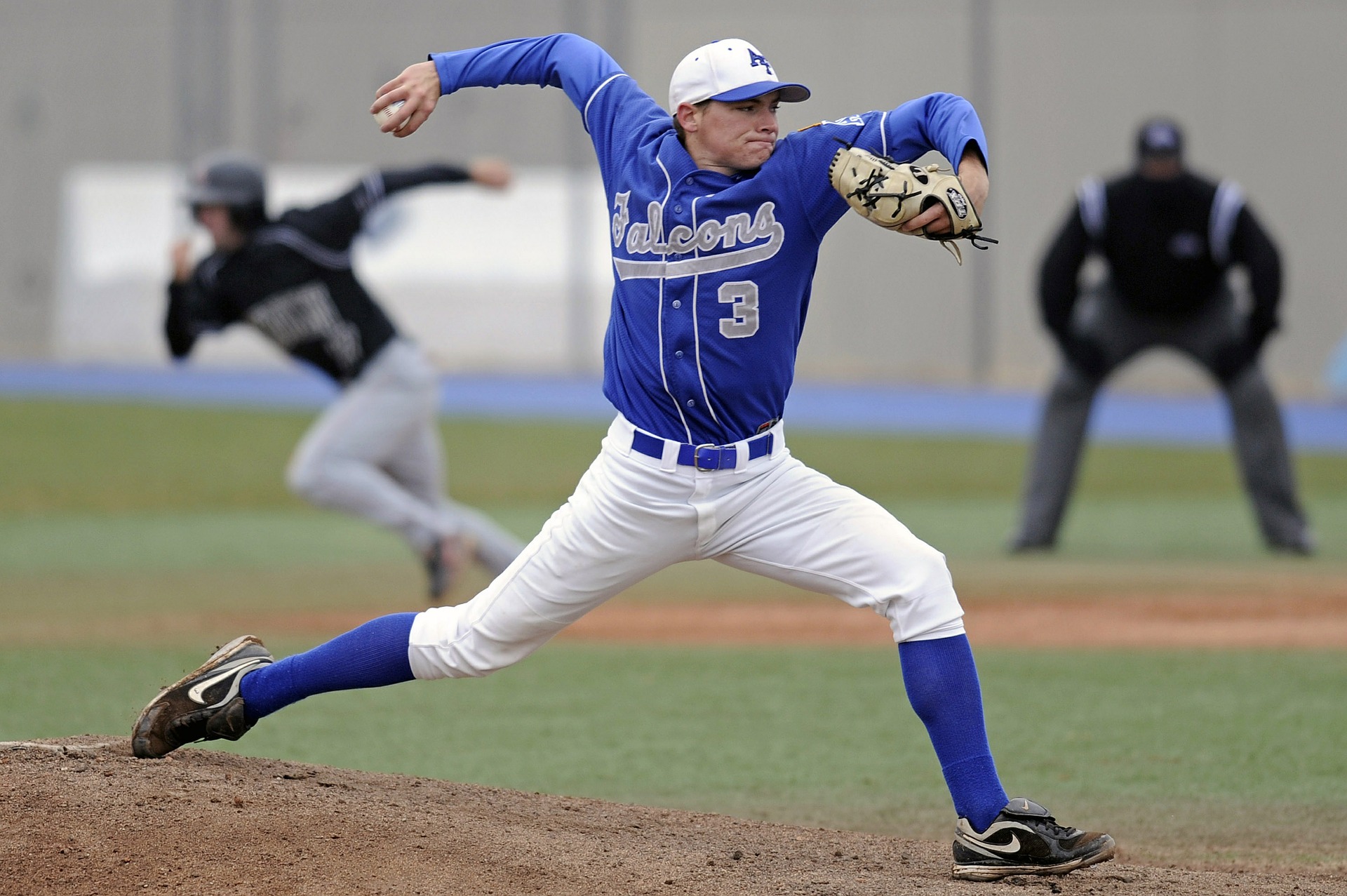

Strength to weight ratio is a key factor to keep in mind while programming for younger kids. As I mentioned in the prior post, kids grow rapidly and without strength training, their muscle power will be left in the dust. Inadequate muscular strength will force kids to rely on their passive restraints during athletic movement. For example: a baseball pitch (or throw) will require strength in the lower body to produce rotation power, strength in the upper back and rotator cuff to maintain scapular and humeral (shoulder blade and upper arm bone) stability, and a strong core to transfer the power from lower to upper body.

This means, Jonny's shoulder and elbow ligaments are going to take a beating if he's throwing with weak muscles.

Another example: changing direction on a soccer field. The athlete must be strong enough to decelerate herself and then accelerate in a new direction. What happens if her hamstrings, glutes, quads, and core aren't strong enough to stop the motion, stabilize her joints, and reapply force in a new direction? (and this just her body weight, mind you, no external load) Strained (at best) knee ligaments, which typically manifests as the nefarious "knee pain," or, at worst, torn ligaments (good-bye ACL...).

A strength training program for a young athlete that uses heavy weights will only continue to teach the athlete to rely on passive restraints. Why? The athlete is already at a disadvantage by way of rapid growth (the strength:weight ratio is already out-of-whack). Therefore, exercises that utilize body weight or very low weights will avoid overloading the muscles and teach the athlete how to actually use their muscle mass.

The next point is tandem- teaching motor control and body awareness to younger athletes will improve their performance quickly. Kids need to understand MOVEMENTS before they can be expected to load those movements. Focusing on technique is crucial during this growing stage as their adjusting to their new bodies. Teaching kids how to use their hips (instead of their knees or lower back) in a squatting, deadlifting, and rotational pattern will benefit them immensely. Drills that include cross body movements (such as rolls and crawls, meaning left and right side have to coordinate) build "movement" bridges across the two hemispheres of the brain. A coordinated brain means a coordinated body.

Balance drills, such as standing on one foot while performing a medicine ball toss, are excellent in training the vestibular systems (inner ear) as well as teaching the brain to understand the feedback being sent by the foot.

The third point, is key. It must be FUN! Older kids often have the maturity to focus. Younger kids... it's debatable. Some kids are rock stars and can focus better than most adults, however, those athletes are few and far between. Most kids between 8-13 have shorter attention spans and lower stamina than their teenage counterparts. Therefore, we try to make the drills as fun as possible, while still teaching them technique and increasing strength. It's like hiding cauliflower in mac-n-cheese. Hide the good stuff with the delicious stuff. Un-fun sessions lead to unmotivated and easily-distracted athletes... which we all know will not advance their potential at all.

To sum it all up:

1. Focus on increasing strength:weight ratio utilizing body weight/light weight variations to teach young athletes to use their muscles.

2. Incorporate coordination and body awareness drills to TEACH MOVEMENT!

3. Keep the program fun!

Strength Training for Youths: It's Really, Really, REALLY Important

At SAPT, the bulk of our population is 13-18 years old; we have a handful of 9-11 year-olds (though that population is growing quickly) and then college age through the adult spectrum. A lot of parents carry misgivings about weight/strength training for kids under 18, a biggie is "it will stunt their growth." Poo-poo on that! What do you think running around a playground is? Physics, that's what is is: loads and forces acting on the body (just like strength training) except playgrounds are much less planned, controlled, and monitored (I have the scars to prove it).

This month we're going to delve into training for youths, even babies and toddlers too, and WHY IT'S REALLY REALLY IMPORTANT for their growth and development.

Today we're will just be an overview of the benefits of strength training for kids whilst the the following posts will illuminate a bit more details of various aspects of training and their importance for childhood development.

Before we jump in, I want to define what I mean by "weight training." I don't mean slapping a barbell on a kid's back or demanding max effort on all exercises. At SAPT, we take the "cook 'em slow" approach where we start with body weight and maybe utilize some light weights (depending on the kid's age and experience level. ALL of our athletes over 15 start squatting with either 10 or 15lbs. I don't care how "experienced they are.) and then we S.L.O.W.L.Y progress them over months and months. We won't even approach a kid's "max" effort level until they're closer to 17-18, and even then, it's only if they've been training with us for multiple years. We use the least amount of stimulus to invoke an adaptation. That, my friends, is how an athlete improves and stays healthy. None of this don't-stop-till-you-drop nonsense.

The following points are in no particular order, rather, this is the way my brain spat them out. They're all equally beneficial and should be coveted by parents for their children.

1. Bone development: Bones grow stronger when stress is applied. Obviously if the stress greatly exceeds what the bone can handle, it will break, but when applied systematically and progressively, the bones will adapt to the stress and become stronger. There's a pretty sweet physicological process seen here:

This is a most-desired process in young kids and teenagers as their bones have not fully ossified (hardened) yet in some places. Progressions from body weight exercises (utilizing isometric holds and negatives to increase the tension without overloading the kid with weight), to light weights, to more challenging weights when the athlete is ready, is a safe and effective way to help kids develop strong bones.

2. Improve kinesthetic awareness and muscular control: The body is pretty complex with lots of moving parts. As kids grow, they develop better control over the force production of muscles (notice how babies tend to wave they're arms and legs around? They're learning how to control the muscles.) and start to learn where their body is in space. Broadly, this is called motor learning and each person has a motor pattern map, if you will. Think of the map as a topographical kind that show hills and valleys and other such features.

A movement map is much the same, instead of hills and valleys, various movement patterns speckle the landscape. Now, I'm going to mix metaphors so stay with me on this one: the movement patterns are similar to computer programs. The brain knows what muscles need to fire for which movements and the forces needed, i.e. throwing a ball overhead, and thus the movement is achieved.

In order to have a successful athlete (or human being for that matter), the movement map must be rich and full of a variety of movement patterns. This way, as the body goes through life, the brain already knows how the body should respond. For example, let's say a kid learns how to throw a ball. The basic program of throwing an object overhead is there. From that program, the brain can easily learn how to throw a baseball or a football because that basic pattern is in place. Taken a step further, the brain could also learn how to perform a tennis serve, since it's the same overhead motion. So a kid who never learns that over head pattern of throwing a ball, will have a tougher time learning overhead motions as they grow.

Side note: "throw like a girl" is a phrase that annoys me. It's not our gender's fault that most** of us aren't taught from a young age like a lot of boys to throw over hand. In conjunction with that, Eric Cressey wrote a cool article about the bony development of shoulders that are exposed to overhead throwing during the ages of 8-13. READ ME, seriously. So there you go, the neurological and physical influence movements have on kids.

Ok, have you drifted off to Facebook yet? No? Good, this is more informative anyway. Weight training (and all the many, many movements that encompasses like rolls, crawls, and the more traditional movements) exposes young athletes to lots and lots of new movements and force production needs. They develop muscular control through the deceleration and acceleration phases of movements as well as how much force the muscles need to generate to create movements. All this enriches their movement maps and sets them up to be successful athletic learners.

3. Maintaining a good strength-to-weight ratio: Kids grow rather quickly. As such, then need to train in a way to increase their muscular strength to go with that growing body. Ever notice how teenagers can be fairly awkward (physically, that is) when they're in the middle of a growth spurt? That's because their muscles haven't caught up to the new length of limbs. Strength training will not only improve muscular control but also teach the brain how to direct the muscles accordingly as they grow. (See Point Number 2 above). It's similar to Milo of Croton carrying a calf up a mountain every day until it was a fully grown ox. What a deliciously ancient example of progressive overload and subsequent adaptation!

4. Strong athletes win: Maybe not the game every time, but athletes that are strong are less susceptible to overuse injuries (due to stronger tendons and ligaments), recover more quickly when injuries do occur, and they are able to adapt to game-time situations (thanks to their rich motor pattern map).

I could continue, but this post is already much longer than I intended it to be. This should convince you that a strength training program designed by responsible, knowledgeable, and maybe a little weird, coaches are exactly what young athletes need to promote growth and successful long term development.

**My dad taught me how to throw and catch a baseball, football, and frisbee. His foresight prevented me from "throwing like a girl." Thanks, Dad!