Strength Training for Youths: Post-Puberty

Last post delved into training strategies for kids pre-puberty. Today we'll discuss weight training suggestions for kids after they've hit puberty. As I stated before, the American Pediatric Association states that puberty starts around 8-13 (girls) and 10-14 (boys). While a 10 year-old girl might be at the same sexual maturity as a 16 year-old girl, physically, mentally, and emotionally, they're vastly different. Therefore, I'm not going to train a 10 year-old the same as I do a 16 year-old.

So what's different?

To be perfectly honest: not much.The same principles of training youths apply across the age span.

1. Address and improve movement quality

2. Improve body awareness, muscular control, and coordination

3. Progressively overload (add weight or increase the difficulty of exercises) movements to produce positive adaptations appropriate to the athlete's physiological status. (Lotta big words for saying challenge the athlete to grow stronger in ways that will not hurt them.)

Coaches and trainers should always address movement above all. If the athlete moves like poop, adding weight is only going to ingrain the dysfunction that could, ultimately, lead to injury.

That being said, there are a few differences between the two age groups. Older athletes will, typically*, learn movements faster. They've been around longer, played more sports (hopefully), and have a fairly rich movement map. Thus, as they learn proper mechanics quickly, they can handle heavier loads sooner. Does this mean max effort? NO! (stop it, stop that nonsense right now!) It means they can SLOWLY add weights over the course of several months/years to their movements. Strength gains are a marathon, not a sprint.

Older athletes are ususally better at maintaining focus during their workouts (though not always...). This allows room for exercises that require more concentration. For example, an older teenager might front squat with a barbell-

-whereas a younger athlete will squat with a light kettlebell. The barbell squat requires (strength, duh) a greater amount of focus as the athlete has to remain tight to stabilize the bar as well as move in a correct squat pattern. Does this mean a 16 year-old moves straight to the barbell? Nope! They have to prove that a) they have the ability to move in a safe squat pattern (hips back, chest up, knees out) and b) they have the strength (core, upper back, legs). At SAPT we will NOT progress an athlete beyond what we think they're capable of just for the sake of using a barbell.

Older athletes can generally handle more complex movements. For example, a heiden to a med ball throw:

Versus our younger athletes who will work on those two movements independently (jumping and landing, and throwing a ball correctly).

Again, and I can't say this enough, progression should be tailored to the athlete's skill and ability. Throwing a barbell on the back of a teenager just because he's 17 doesn't mean he's able or ready to squat with that barbell. Being 17 does mean that, if he's demonstrated good movement and strength, we can probably progress him to the barbell (we wouldn't do that for a younger kid. They would just continue with kettlebell variations until they've grown a bit more).

The basic principles of training youths across the age-range are the same:

1. Address and improve movement quality

2. Improve body awareness, muscular control, and coordination

3. Progressively overload (add weight or increase the difficulty of exercises) movements to produce positive adaptations appropriate to the athlete's physiological status.

Older athletes will generally be able to:

1. Learn and load movements more quickly than younger athletes

2. Perform exercises that require more concentration

3. Perform more complex exercises

Overall, training youths is like vanilla ice cream: same flavor, different sprinkles.

*I say "typically" because we've seen older kids who have such poor motor control that we have to start them out as we would a 9 year-old and progress them accordingly. What a child does during their infant and toddler years matters! (oooo, teaser for next week!)

Strength Training for Youths: Pre-Puberty

Last week's post listed persuasive (I think so anyway) reasons why kids should enroll in a strength training program. In that post is also a definition of a smart, sound training program. If you can't remember, here's the refresher; it involves none of the max effort, grunting/screaming/shouting version that, unfortunately, is the stereotype of our industry. Parents: NOT ALL TRAINING PROGRAMS ARE CREATED EQUAL!!!

Matter of fact, if you find your 9 year-old doing the same workout as your 16 year-old, something is dreadfully amiss. This post and the next will shed light on the differences that you should see between age groups, broadly, pre-puberty and post-puberty. Now, one thing to keep in mind as you read, these are general guidelines that apply to most of the population. There will be some puberty-stricken kids that are not prepared to train like their peers (meaning, they will be regressed considerably) and there will be some young kiddos who's physical development far exceeds their peers (though it does NOT mean they're ready for large loads; instead they'll have more advanced bodyweight and tempo variations.).

Right, let's hop in.

According to the American Pediatric Association, puberty starts between 8-13 for girls, and 10-14 for boys. For today's discussion, let's assume 15 years is the game changer in physical development. In my experience, kids under 15 still are pretty goofy and often don't have the muscular development that a 15 or 16 year old will (boy or girl). Between 8-15 a LOT of growth happens (and beyond for most boys, but we'll ignore that for now). That segues nicely into my first point:

Strength to weight ratio is a key factor to keep in mind while programming for younger kids. As I mentioned in the prior post, kids grow rapidly and without strength training, their muscle power will be left in the dust. Inadequate muscular strength will force kids to rely on their passive restraints during athletic movement. For example: a baseball pitch (or throw) will require strength in the lower body to produce rotation power, strength in the upper back and rotator cuff to maintain scapular and humeral (shoulder blade and upper arm bone) stability, and a strong core to transfer the power from lower to upper body.

This means, Jonny's shoulder and elbow ligaments are going to take a beating if he's throwing with weak muscles.

Another example: changing direction on a soccer field. The athlete must be strong enough to decelerate herself and then accelerate in a new direction. What happens if her hamstrings, glutes, quads, and core aren't strong enough to stop the motion, stabilize her joints, and reapply force in a new direction? (and this just her body weight, mind you, no external load) Strained (at best) knee ligaments, which typically manifests as the nefarious "knee pain," or, at worst, torn ligaments (good-bye ACL...).

A strength training program for a young athlete that uses heavy weights will only continue to teach the athlete to rely on passive restraints. Why? The athlete is already at a disadvantage by way of rapid growth (the strength:weight ratio is already out-of-whack). Therefore, exercises that utilize body weight or very low weights will avoid overloading the muscles and teach the athlete how to actually use their muscle mass.

The next point is tandem- teaching motor control and body awareness to younger athletes will improve their performance quickly. Kids need to understand MOVEMENTS before they can be expected to load those movements. Focusing on technique is crucial during this growing stage as their adjusting to their new bodies. Teaching kids how to use their hips (instead of their knees or lower back) in a squatting, deadlifting, and rotational pattern will benefit them immensely. Drills that include cross body movements (such as rolls and crawls, meaning left and right side have to coordinate) build "movement" bridges across the two hemispheres of the brain. A coordinated brain means a coordinated body.

Balance drills, such as standing on one foot while performing a medicine ball toss, are excellent in training the vestibular systems (inner ear) as well as teaching the brain to understand the feedback being sent by the foot.

The third point, is key. It must be FUN! Older kids often have the maturity to focus. Younger kids... it's debatable. Some kids are rock stars and can focus better than most adults, however, those athletes are few and far between. Most kids between 8-13 have shorter attention spans and lower stamina than their teenage counterparts. Therefore, we try to make the drills as fun as possible, while still teaching them technique and increasing strength. It's like hiding cauliflower in mac-n-cheese. Hide the good stuff with the delicious stuff. Un-fun sessions lead to unmotivated and easily-distracted athletes... which we all know will not advance their potential at all.

To sum it all up:

1. Focus on increasing strength:weight ratio utilizing body weight/light weight variations to teach young athletes to use their muscles.

2. Incorporate coordination and body awareness drills to TEACH MOVEMENT!

3. Keep the program fun!

Why Train In-Season?: Strength and Power Gains

Hopefully by now, you've read about the signs and reversal of overtraining. Now let's look at why and how to train intelligently in-season. A well-designed in-season program should a) prevent overtraining and b) improve strength and power (for younger/inexperienced athletes) or maintain strength and power (older/more experienced lifters).

First off, why even bother training during the season?

1. Athletes will be stronger at the end of the season (arguably the most important part) than they were at the beginning (and stronger than their non-training competition).

2. Off-season training gains will be much easier to acquire. The first 4 weeks or so of off-season training won't be "playing catch-up" from all the strength lost during a long season bereft of iron.

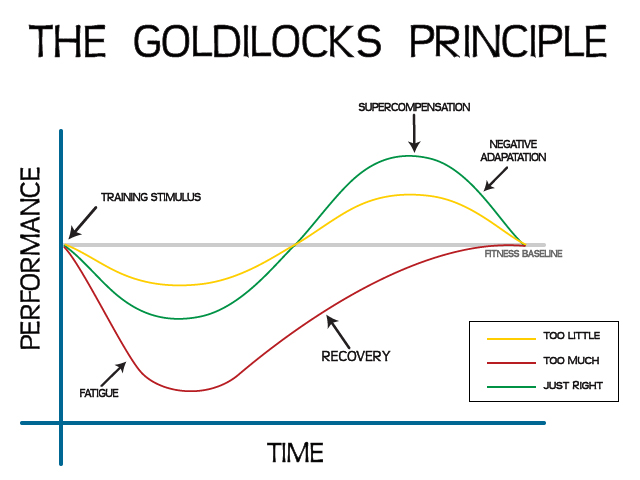

I know that most high school (at least in the uber-competitive Northern VA region) teams require in-season training for their athletes. Excellent! However, many coaches miss the mark with the goal of the in-season training program. (Remember that whole "over training" thing?) Coaches need to keep in mind the stress of practice, games, and conditioning sessions when designing their team's training in the weight room. 2x/week with 40-60 minute lifts should be about right for most sports. Coaches have to hit the "sweet spot" of just enough intensity to illicit strength gains, but not TOO much that it inhibits recovery and negatively affects performance.

The weight training portion of the in-season program should not take away from the technical practices and sport specific. Here are a couple of things to keep in mind about the program, it should:

1. Lower volume, higher intensity-- this looks like working up to 1-2 top sets of the big lifts (squat or deadlift or Olympic lift), while maintaining 3-4 sets of accessory work. The rep range for the big lifts should be between 3-5 reps, varied throughout the season. The total reps for accessory work will vary depending on the exercise, but staying within 18-25 total reps (for harder work) is a stellar range. Burn outs aren't necessary.

2. Focused on compound lifts and total body workouts-- Compound lifts offer more bang-for-your buck with limited time in the weight room. Total body workouts ensure that the big muscles are hit frequently enough to create an adaptive response, but spread out the stress enough to allow for recovery. Note: the volume for the compound lifts must be low seeing as they are the most neurally intensive. If an athlete can't recover neurally, that can lead to decreased performance at best, injuries at worst.

3. Minimize soreness/injury-- Negatives are cool, but they also cause a lot of soreness. If the players are expected to improve on the technical side of their sport (aka, in practice) being too sore to perform well defeats the purpose doesn't it? Another aspect is changing exercises or progressing too quickly throughout the program. The athletes should have time to learn and improve on exercises before changing them just for the sake of changing them. Usually new exercises leave behind the present of soreness too, so allowing for adaptation minimizes that.

4. Realizing the different demands and stresses based on position -- For example, quarterbacks and linemen have very different stresses/demands. Catchers and pitches, midfields and goalies, sprinters and throwers; each sport has specific metabolic and strength demands and within each sport, the various positions have their unique needs too. A coach must take into account both sides for each of their positional players.

5. Must be adaptable --- This is more for the experienced and older athletes who's strength "tank" is more full than the younger kids. The program must be adaptable for the days when the athlete(s) is just beat down and needs to recover. Taking down the weight or omitting an exercise or two is a good way to allow for recovery without missing a training session.

A lot to think about huh? As a coach, I encourage you to ask yourself if you're keeping these in mind as you take your players through their training. Athletes: I encourage you to examine what your coach is doing; does it seem safe, logical, and beneficial based on the criteria listed above? If not, talk to your coach about your concerns or (shameless plug here, sorry), come see us.

Tackling Technique: How to (Safely) Pummel Your Opponent

Today's special guest post comes one of our athletes, Dumont, who's played Rugby professionally and currently coaches for the Washington Rugby Club. Given his past history and present involvement in Rugby, and the fact that the dude is a monster, it stands to reason that he knows a thing or two about pummeling an opponent. He graciously offered his expertise on tackling to share with everyone here on SAPTstrength. Here he provides many practical tips on not only executing an EFFECTIVE tackle, but also how to do so in a safe and concerted manner. Hit it Dumont!

The NFL combine is just days away, and many aspiring athletes will be jumping, running, and lifting in an attempt to impress potential employers. One skill that not showcased at the NFL Combine is tackling. Some could argue the tackle is a lost art in today’s NFL game. Yes, we see plenty of big hits each week, and as a result of those big hits, the NFL is attempting to regulate the tackle zone in an effort to protect its players. However, with the increase in big hits, what we are actually seeing as is many defenders forgetting the fundamentals and failing to finish the tackle. The result is we see a lot of missed tackles on Sunday, and a lot of needless injuries. The art of the proper form tackle has been lost.

What is a proper form tackle? A form tackle requires the tackler to use their entire body. Eyes, arms, shoulders, core, and legs are all engaged in an effort to bring a ball carrier to the ground in an efficient and safe (well as safe as a tackle can be) manner. While it may not result in the big “jacked up” highlight hit we’ve become accustomed to seeing on television, a form tackle will bring a ball carrier to the ground, and stop them in their tracks every time.

Before we break down the parts to making a tackle let’s point out the first step, take away a ball carrier’s space. The closer a tackler can get to the ball carrier the less opportunity they have to shake and get out of the way. Close the space to within a yard, of the ball carrier and now the tackler is in the tackle zone. Closing the space also allows the tackler to use their body like a coiled up spring that can explode into contact at the right moment.

Let’s break down the tackle into parts and make it easier to digest. The first part is the eyes. Before one can make a tackle, a player needs to spot their target, and know what they are aiming for. The tackler must remember to keep your eyes open and spot their target. This will also help to keep their head up. Keeping their head up is key not just so they can see, but also for safety. It keeps the back in a straight line and helps to protect the neck.

Two keys a tackler should remember when using their eyes:

- Keep them open- sounds simple but you’d be surprised at how easily they close just before impact

- Focus on the ball carrier’s core- they can move their legs, arms, and heads, but where their core goes, the entire body goes. Focusing on the core will lead to the tackle point.

The second part of the tackle is the arms and shoulders. Many people have different ideas of what to do with their arms when making a tackle. Often times tacklers start with their arms out wide and it looks like they are trying to bear hug their opponents. While this is effective in making a tackler look big and fierce, it’s actually inefficient when it comes to making the tackle and dangerous as it exposes the weaker muscles in the arm. When a tackler’s arms are out wide it creates “weak arms,” we teach ball carriers to run towards those open arms because it’s much easier for them to break through. By keeping the arms in tight and the hands above your elbows the tackler engages the shoulders and the arms creating a strong base to enter the tackle zone.

Here are the keys for the arms when making a tackle.

- Imagine creating a TV screen with your hands, and the ball carriers core is the show you want to watch.

The next part to the tackle equations is the legs. First we’ll focus on the feet. The lead foot is most important. Step towards the ball carrier using the lead foot. This brings the tacklers body with them, and allows them to use their entire body and keeps the body compact and coiled like a spring.

Keys to good footwork

- Step towards the ball carrier taking away their space

- Do not cross your feet

- Take short controlled steps not to overextend yourself.

Once the feet are in position, we need to focus on getting the rest of the legs into proper tackling position. This is done by bending at the knees, and creating a powerful base. By bending at the knees a tackler engages their legs and they are coiled and ready to explode. This will also keep the tackler low and allow them to attack the ball carriers core and legs. We do not want to tackle ball carriers up around the chest and arms, it’s too easy for them to break through when we get that high. Bending at the knees also gives the tackler the agility to move left, or right should the ball carrier change direction. Remember to keep your head up and your eyes open during all this.

So far we’ve covered a lot of stuff, so let’s take a moment and give a quick rundown of everything to make sure every is on the same page.

- Eyes Open

- Arms in tight, hands up

- Lead foot forward

- Bend at the knees

- Heads up

This puts an athlete into the perfect tackling position. To make contact the tackler wants to pick a side of the ball carrier’s body and attack that with their shoulder. The head should be placed on the side of the ball carrier’s body, not across it. This protects the tackler from being kneed or elbowed in the head, and reduces the possibility of injury. Using your lead foot step in, make contact with the shoulder.

A good rule to remember is “cheek-to-cheek.”

The next part of the tackle is the arms. We already have our arms in tight and our hands are up. Once the tackler makes contact with the shoulder we want to punch with the arms. Bring the arms up keeping them close and wrapping them around the ball carriers body, pulling the ball carrier in tight.

The final part is engaging the legs and drive forward. Once the tackler made contact with the shoulder and wrapped up the ball carrier with their arms, start pumping the legs. Drive forward and force the ball carrier to the ground. Use the ball carriers body as a pillow to land on. This will bring the ball carrier to the ground.

Form tackles are effective. The main key is putting the body into the correct position. Take away the ball carrier’s space, head up, eyes open, arms in, hands up, knees bent, then explode into the contact point, wrap the arms and drive the legs.

Thanks Dumont! Hopefully you all learned a li'l sumthin' sumthin' about tackling (safely and effectively... as opposed to just mindlessly throwing your body at your opponent). Proper technique will go a long way to both helping prevent injuries and winning games. And just for fun, here's a video of football vs. Rugby:

And if you want to smile: *Note* I love our soccer players! I just thought the video was funny.

Femoroacetabular Impingement and Football Kickers. "That's Why My Hip Hurts!"

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) syndrome has become more widely recognized thanks to folks such as Kevin Neeld, Eric Cressey, Mike Reinold, and a plethora of other smart coaches. FAI is a common* syndrome/injury in athletics and football kickers are especially susceptible due to the nature of the violent hip flexion during the kick off/punt. At the end of the article I'll put some links for more information regarding testing for FAI, research regarding FAI, and other resources. The last two posts have been marathon length, so we'll keep today short and to the point. What is FAI?

FAI is essentially:

Femoroacetabular impingement or FAI is a condition of too much friction in the hip joint. Basically, the ball (femoral head) and socket (acetabulum) rub abnormally creating damage to the hip joint. The damage can occur to the articular cartilage (smooth white surface of the ball or socket) or the labral cartilage (soft tissue bumper of the socket).

from www.hipfai.com. Athletes that participate in activities that include repetitive hip flexion and internal rotation or folks who have super crappy mobility in their hips are at a higher risk of developing hip issues. Also, athletes who are constantly in a state of anterior pelvic tilt (aka: nearly every one of them) are also primed for some impingement.

Now, look at a football kick off. Check out the crazy hip flexion and internal rotation (when his leg crosses over the midline of his body around the :29-:31 mark).

Can you see how a kicker might develop a problem? Especially if they're not a physically STRONG kicker?

Just so you know, FAI comes in three flavors, none of which include chocolate or vanilla:

CAM- bony overgrowth on the femoral head (ball)

Pincer- body overgrown on the acetabulum (on the socket on the pelvic bone)

Mixed- a lovely combination of both.

How do I spot FAI?

IMPORTANT: Remember, unless you're a doctor, you CANNOT DIAGNOSE. The following are merely indicators that something is amiss. A visit to the doctor and possibly the Wonder Machine (MRI) will be the only sure way to diagnose any pathology.

Now, as a coach/player it's important to be aware of FAI and be on the look out for the symptoms. FAI will most likely manifest on the kicking leg simply because it is subject to that the crazy-hip-flexion. Bilateral FAI is found more often in sports with bilateral hip flexion such as hockey or powerlifting. However, this doesn't mean that both sides can't be affected, so be on the vigilant!

There are two simple tests that you can do yourself (though I STRONGLY recommend you see a professional..cough, cough.)

One is the Faber Test.

The other is a supine hip flexion with internal rotation of the femur.

If this lights you up, and you're also experiencing the symptoms below, you should probably high tail it to a person with the initials, "M.D." after there name.

A few other symptoms that as either a coach or a player you should be on the watch for (and probably perform the aforementioned tests):

1. Pain with squatting below 90 degrees. Speaking from experience, it feels "pinchy" in the front of the hip, just a smidge medial (inside) of the pelvic bone.

2. Pain with internal rotation and hip flexion. For example, getting into a car leading with the affected leg (one has to flex the hip to sit and internally rotate the hip to slide into the car).

3. Another potential, but not always present, is a history of repeated sports hernias or groin pulls.

4. As a coach, if you're watching a player squat, if one hip seems to drop more than the other. The hip that DOESN'T go as low, will be the affected hip. The player will also weight shift towards the affected side as they stand up from the bottom of the squat.

Don't be stupid and keep training through this pain (again, I speak from experience). Some of the associated symptoms/pathologies of FAI include: cartilage damage, labral tears, (the labrum helps keep the hip stabilized. It's really important.) early on-set osteoarthritis of the hip, sports hernias, and low back pain.

Speaking as someone who has bilateral FAI (and the labral tears), it sucks. Don't be a hero, go to the doc if you're experiencing these symptoms.

What are the Implications of FAI?

An athlete the has impingement of their hip will have limited hip flexion range of motion (ROM) on the affected side. What does this mean for a football kicker?

- No more squatting. Think about it: 1) hip flexion ROM is going to be limited on one side. 2) If you're bilaterally loaded, as in a squat, one hip will drop lower than the other, and if the hips can't move independently, as they could in a lunge, you're going to impose some wonky forces on the spine. 4) Wonky forces on the spine eventually lead to injuries and pain. Not the best game plan. (You could get away with squatting above 90 degrees, but no sense in playing with tigers if you don't have to.)

- There's a study found here that looked at hip flexor strength a group of people with diagnosed FAI. The study found that those with FAI had weaker hip flexors than the controls. (I can personally attest this is true.) Whether the people had FAI because their hip flexors were weak, or the hip flexors became weak with FAI onset, doesn't matter for this discussion. What does matter is that the HIP FLEXORS ARE WEAK! Now, in a football kicker, what's the main group of muscles used to kick? HIP FLEXORS! Do you see a problem? If a coach is oblivious to this, yelling at a kicker to kick harder isn't going to do much. Also, without proper training (perhaps some focused work for the hip flexors such as SL marches or hanging leg raises), other muscles are going to take over for the lack luster hip flexors and then you have a whole new set of problems.

- Hip dominant exercises (deadlifts, RDLs, glute bridges, and swings) and single leg work (split squats, step back lunge variations, step ups (as long as the hip stays >90 degrees), and single leg RDLs) must be the bulk of lower body work. All of these tend to keep the hip out of excessive hip flexion + internal rotation. They also hammer the glutes, which will help keep the femur from gliding forward in the socket and causing more ruckus in the pelvic region. Food for thought: I've personally found that walking lunges/forward lunges tend to make my hip ache as do back-and-feet elevate glute bridges.

- As far as corrective work goes, hammer hip stabilization and anterior core. Low level glute work such as double- and single leg glute bridges, monster walks, and bowler squats will challenge the smaller stabilizers of the hip. This in turn will keep the femoral head from gliding around and causing more damage. Anterior core is necessary to, hopefully, control anterior pelvic tilt (which most athletes sit in anyway) and even, possibly, pull the pelvis a little posteriorly. This will, again, keep those bony overgrowths from grinding on each other. Here's a great video by my better half on anterior core progressions.

Another note: I've found that single leg anterior core exercises (such as a single leg plank) bother my hips. Be mindful and if it hurts, don't do it.

Wow, so I broke my promise of writing a lengthy post. However, this is an EXTREMELY important issue that many kickers are faced with (we've had one walk through our doors, not to mention the other handful of other athletes from a range of sports).

*Just chew on this; a recent study of asymptomatic people found that of the 215 male hips (108 patients) analyzed, a total of 30 hips (13.95%) were defined as pathological, 32 (14.88%) as borderline and 153 (71.16%) as normal. That means potentially 1 in every 3-4 males have some sort of underling hip "thing" going on. (thanks Kevin Neeld!) That's a lot.

As promised here are some links for more information:

Post on Mike Reinold's site with more in-depth diagnoses.

Kevin Neeld has a bunch: 1, 2, and 3 (and the one linked above)

And Tony Gentilcore, who does a fantastic job communicating a complex topic to the lay population, while adding some humor to boot.

Whew!

Top 5 Dietary Changes

In case you haven't noticed, the theme of this month is oriented towards achieve the physical goals (be it body composition changes, athletic performance, or increasing levels of Jedi Mastery) that are most frequently established January 1. On Wednesday, Jarrett covered 6 rules/tips to enhance the overall efforts to achieving said goals. For those of you who like to click on links, this post is for you; for today, I have 5 changes specifically for the kitchen. Why the kitchen? Because what goes on in the kitchen can make or break your physical fitness goals.

Trying to train and perform (be it for physique or performance, or both) on a woefully crap-o-licious diet is like trying to throw a 10lb medicine ball from half court and expect to make the basket... try it and let me know if it works. Sure, you can get by on eating cheetos, candy, and guzzling soda and "feel fine," but sooner or later my friend (I'm looking at you teenagers...) it WILL catch up to you. If you don't believe me, just take a gander at this article about nutrition in the NBA. Just because you look invincible on the outside, doesn't mean you are invincible on the inside.

To our readers with some, shall we say, years of experience, who may be struggling to accomplish your goals but can't...seem...to...quite...get.....there.... BAH! (throws hands up in frustrated desolation) Do not give up hope! Today we'll lay out some simple, yet effective, dietary changes that can turn the tide when it comes to battles of the health nature. The following suggestions are applicable to the teenager who needs to fuel athletic competition and practice as well as their parent(s) who is seeking to improve overall health and stamina.

Public Service Announcement from the Desk of Kelsey Reed: These are all small changes. I would encourage to try one or two changes a week (or 2 weeks) in order to acclimate to the alterations. I don't recommend trying to overhaul everything at once, unless you're confident it won't drive you crazy, since incremental changes are much easier to adjust to than large ones. Rome wasn't built in a day and neither is converting a not-so-healthy lifestyle into a healthy lifestyle. It takes time and patience. Read on!

1. Learn how to read food labels

Read this --> Kitchen Ninja Skillz. While this is not a direct food change, the ability to read and interpret food labels will greatly enhance your discernment when it comes to "healthy" foods. Many foods are labeled as such, but in fact, they lie. The ingredients is where the truth resides! Ignorance of what's in your food sets you up for failure. Knowledge is power! (and in this case, health!)

2. Reduce overall sugar intake

Now, you can go commando on all sugar and eliminate it entirely (with the exception of fruits. Some diets will tell you to do that, I'm not so sure about the wisdom in that. When a diet calls for you to eliminate an entire food group (outside of a medical need), there's something wrong with that.) or eliminate the extra processed sugar-laden foods first, and then work to replacing said foods with whole, natural foods. This is a 2-for-1 deal in that, if you're whittling down the amount of processes sugar you eat, you'll also be removing the fake food crap and increasing your real, whole food intake. Bonus!

There are numerous studies out there that demonstrate the negative effects of added/refined sugars (here's a small sampling). Imagine how great you'll feel if you take out all the junky-junk! This is applicable to both sides of the population (those seeking to gain weight and those seeking to lose) since a super high sugar intake can hijack glucose metabolism and processes (think back to the NBA article about Dwight Howard, he was having all sorts of neurological issues that were affecting his performance!).

Perhaps the first step is to not use creamer and sugar in your coffee, instead try either plain milk and a touch of honey. I prefer stevia with a little bit of coconut oil. Swap out baked desserts (like cookies and cakes) and instead try a baked apple, raw fruit, or maybe some yogurt with frozen berries (or if you wanna get snazzy with your yogurt). There's even a way to make your own sorbet! There are SO many options and recipes out there that do not use processed, refined sugar and are a sweet, healthy replacement for desserts and snacks. EXPLORE!

Take a gander at what you eat daily, it should be fairly easy to identify which foods contain the most refined sugar (since you know how to read food labels right?). Ensure that you examine what you drink as well. Fruit juices are, more often than not, the opposite the pancea of health. Replace those foods/drinks with whole foods, i.e. fruits for baked goods, water/tea for sodas, etc. Again, make the adjustments small and manageable.

3. Eat more vegetables

I've said it over and over and over. EAT MORE VEGETABLES! I'm not going to belabor this point too much, because, if we're honest with ourselves, we ALL KNOW THIS, but choose to ignore the little Jiminy Cricket of Nutrition on our shoulders.

Let's do a quick list on why this will make life better:

- Vegetables are bulky and will make you feel full on less calories (and the calories you do intake are JAM PACKED with nutrients that can only enhance your bodily functions). Eating less calories = weight loss.

- Phytochemicals, minerals, vitamins, and compounds with funny names are found in abundance throughout the vegetable world. I'm not going to get into all of them, you can read some specific things here and here if you're so inclined. Simply, if you're body's internal functions (think metabolism and all those various processes) are working properly, the more external functions (think exercise and recovery) are going to be a cinch.

- Fiber and well lubed tubes. Need I say more?

How does one go about this? Small start: Add one vegetable to each meal (that didn't already have one). This could be tossing in spinach and chopped veggies to your scrambled eggs in the morning, replacing rice with cauliflower "rice," (cauli "rice" instructions),ordering a side of steamed vegetables instead of fries at a restaurant, if you like to be sneaky you can puree some steamed cauliflower or broccoli and hide it in meatloaf, or simply, just adding some steamed or roasted vegetables to your meal. You can make a whole, huge batch of roasted veggies and just scoop out a few spoonfuls throughout the week.

4. Drink water, lots of it

Depending on where you read about the body, it's anywhere from 70-80% water. Don't you think that means we need to ingest a lot of it in order to function optimally? Water does the following:

- Hydrated joints are happy joints. Painful joints hinders training.

- Hydrated kidneys (which process toxins and such) are happy kidneys. Dehydrated kidneys cannot do their jobs well, therefore, they must call upon the liver to help out. Whilst the liver is busy processing toxins and such, stored body fat just hangs out (and accumulates depending on your caloric intake). Hydrate your kidneys!

- Promotes weight loss via appetite suppression. Sometimes the "hunger" cue gets confused with the "thirsty" cue thus you eat more than you need... and we know what that leads to.

How do we do this? Grab a water bottle, fill it, and drink at least two of them throughout the day. Combine that with the normal volume of liquid and you should be good to go. Essentially, you should be peeing a light yellow to clear. That's when you know you're drinking enough.

5. Get tougher

Seriously, the tips above aren't anything earth-shatteringly new. And they really aren't that hard to begin implementing into your daily life, especially if the changes are small, manageable, and incremental. Stop seeking the "quick fix," or the new "diet" that leads to miraculous body changes.

Suck it up. Life is tough and things worth having require hard work, sacrifice, and perseverance.

I'll admit (this probably makes me a horrid person according to some schools of thought) but I have very little compassion or sympathy for people who moan and groan about their lack of progress who do NOTHING to change. As a coach, my job is to help people reach their goals, I'm ALWAYS delighted to do so and love encouraging people to continue striving to better themselves. However, I don't coddle. If you're an capable, reasonably intelligent adult, you don't need me (or any coach for that matter) to hold your hand. I'm not Sam from above, I'm more like:

Elrond will fight with you, give you advice, but he won't lie to you. And he certainly won't hold your hands. How do you teach a kid to swim? You don't hold them up the whole time or give them floaty things forever do you? NO! You let them struggle and strive until they figure it out. The same principle applies to life-style changes. IF you're relying on others to "make" you change, you're setting yourself up for failure. You are responsible for your body, take ownership.

Are you going to have bad days? Yes. Will you mess up? Yes. So what? Shake it off, and get back on track. Wallowing helps you none.

Get up. Take action.