Q & A: How to Begin A Running Program

Q: "My son, a lacrosse player, would like to try out for High School Cross Country this upcoming Fall. Any suggestions on how he should prepare? He currently has very little endurance so I thought it would be best for him to get started before the actual season begins."A: Great question. While my recommendations will vary depending on the individual (injury history, running history, other sports they may be playing currently, how much time they have to prepare, are they an elf, dwarf, wizard, or human, etc.), here are some general guidelines for the healthy, human, individual:

1. Start NOW

You hit the nail on the head when you mentioned it would be best for your child to start now.

Too frequently I see people wait until the last minute to begin a running program, and then, one week before the season (or a race), they have a moment of "Oh crap I haven't been running but practice starts 5 days from now, how about I go jump into a thousand mile run to prepare" and then they jet off down the neighborhood.

This concept may work when applied to a procrastinating college student who crams for exams at the last minute (not that I would know anything about that), but not so much with regards to running. Attempting to shove in last-minute, high volume, running sessions one week before the season as a sure-fire way to accrue an injury (not that I know anything about that, either...), which obviously doesn't help your son's chances of making the cross country team.

Slow and steady really does fit the bill with regards to running (and lifting) programs. Don't delay any longer in getting started, and start with a very short distance. Resist the urge to do too much, too soon.

2. Begin with "Rectangle Sprints" on Grass

This is my all-time favorite way to ease people, including myself, into running. It's easier on the joints compared to running on concrete, it's not terribly taxing, and it sets the stage quite nicely for future training.

How ToDo It

Find a soccer field (roughly 100-110yds long), and "sprint" the straights, then walk the sides. The sprints should NOT be a maximal effort run, but around 85% top speed while focusing on good technique and steady breathing. After you walk the endline, you'll then run down the other sideline. Walk the endline, and.....congratulations, you've just discovered why these are called rectangle sprints.

If, upon walking the endline and arriving at the next corner, you find that your heart rate is still jacked up through the roof, take some time to let it slow down. Ideally it will be back to 140bpm before you initiate the next sprint.

Frequency: 2-3x/week

Repetitions: 4-12. Begin by performing no more than four total rectangles, which would be eight total sprints (not kidding, that's all you need for Day 1). Increase the total rectangles by one each session, capping it out at twelve.

3. Next, Add Hill Sprints

Hill sprinting has to be my favorite form of conditioning. Super easy on the joints, challenging, and won't leave you feeling too banged up.

You can typically find a good hill near a lake, reservoir, or school. Google Maps is your buddy in this department. Try your best to find a GRASS hill, and one that is relatively steep. Don't worry if it's a super long hill; you can always start partway up it if the hill is crazy long (you don't want the sprint to last longer than twelve seconds).

I actually wrote out my guidelines for hill sprinting HERE, so click the link for the "How To."

Begin these roughly 1-2 weeks after initiating the rectangle sprints, and start with a frequency of 1x/week, never exceeding 2x/week.

Also, of note: Just because hill sprints are easy on the joints and don't tend to affect recovery as much as other "cardio" modalities, they are downright brutal, and not for the faint of heart.

4. Begin Steady State Running, Following the Rule of 20%

Finally, add steady state running. There are so many strategies one can use here, but to keep it simple, start off with a 20-30 minute run. This can be done 3-5x/week, starting on the low end and carefully monitoring recovery.

The 20% rule is a MUST when it comes to designing and implementing conditioning programs.

Never increase the total time, or distance, by more than 20% each session. So, for example, if you run for 30 minutes on Day 1, don't run for more than 36 minutes on Day 2. Or, if you perform 750 total yards of shuttle runs on Day X, don't do more than 900 total yards of shuttles on Day "X+1." (How bout that algebra, hmmm?)

This will allow you to improve quite a bit while minimizing the risk of injury.

Closing Thoughts

- What about HIIT (High Intensity Interval Training)? This is a topic for an entire other post, but in the meantime, don't worry about it. HIIT certainly has its place, but, for now, stick to the three modalities listed above.

- Once you move into your steady state work, feel free take a break on the days you feel particularly "beat up" and do some rectangle sprints instead. Personally, I love them for "in-between" days and often find that they invigorate me for my subsequent sessions compared to taking the day off completely.

- You can still supplement your steady state running with hill sprints 1x/week to give the joints a break (in fact, I recommend this).

- Take at least two days off a week from running, during which you can......see the next point.

- Be sure you're involved in a quality resistance training program. Amongst the running world, this this has to be one the most underappreciated components of a quality running program.

Sports Are Healthy Right? by Tadashi Updegrove

Continuing from my last post about the do’s and don’ts of an intern, SAPT received someone who exemplified pretty much exactly what I felt a good intern should be. For the past semester Tadashi has made an impact on SAPT through his knowledge, coaching, and ability to learn and apply. In his brief time here he became a colleague and a good friend. Unfortunately, his time at SAPT has come to an end and he has decided to take his talents to South Beach and by South Beach I mean College Park, Maryland to pursue an internship with the S & C department. With that said, here is Tadashi’s final task for completing his time at SAPT.... As a Kinesiology major, I was required to enroll in a “Senior Seminar” class this past semester, where we basically got in a big group and discussed health. Most discussions were centered around the importance of health, how we can inspire others to be healthy, and the future of health in the United States and the world. As many of my fellow classmates declared their own personal mission statements to become soldiers in the war against obesity, or how to combat the big tobacco companies, I sat quietly in the corner, hoping I didn’t get called on. Then I got called on:

“Tadashi, why are you so interested in health?”

After stumbling over my words I finally managed to utter something like “err… I, um... I’m not.” I went on to explain that health was not my primary interest. What I was interested in was sports and sports performance. I wanted to understand how the human body adapts so I could understand how to manipulate the applied stimuli to make someone stronger, jump higher, hit harder, and pick up heavier things.

Then I was approached with a follow up question:

“Well, sports are healthy right?”

I don’t know how I feel about that one. Sure being physically active and exercising is healthy, but after looking through countless research articles it’s hard to ignore the high percentages of participant injury in sports. Competitive lifting, both powerlifting and weightlifting, ranks at the low end of participant injury with something between 40%-50% (Yup, ½ of participants getting injured apparently is low compared to other sports). The NFL is under scrutiny right now because of the concussion rates and the violent nature of the game. I know the NFL is easy to hate on when discussing health and safety because… well it’s football, and the game involves Hulk-Smashing people against their will.

But football players aren’t the only ones getting hurt. Even the concussion rates in girls’ lacrosse are high enough to raise concerns about helmet requirements. Take a look at ACL injuries and you’ll find that the overwhelming majority of ACL tears occur because of non-contact situations. ACLs tend to rupture during a sprint, a jump landing, decelerating, or change-of-direction task. Athletes in sports that demand a high volume of these tasks are placed at a higher risk of injury. Think soccer, volleyball, basketball, etc.

During my experience working with the SAPT coaches and athletes, I began to realize more and more that training for performance is training for health. Learning to squat with the knees out and the hips back makes you more of a beast because you get more recruitment of the glutes and your legs are placed in a structurally ideal position to produce force into the ground. This also happens to be the healthiest position for your knee joint by reducing the load to the medial compartment. Bracing the midsection during a lift will increase performance because of an improved transfer of force between the upper and lower body. This ability to create a rigid torso also happens to be the best way to keep your spine from folding in half under load. Similar performance and health benefits can be said about keeping the scapulae retracted during rows or tucking the elbows during a pushup.

I played lacrosse and ran track in high school, and now compete in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu/submission grappling, and like many athletes in other sports, have come to understand that injuries are just part of the game. Most athletes can expect to get banged up here and there. Sometimes, unfortunately, they’ll get hit with a more serious injury that takes them out for a length of time that really puts their patience (and sanity) to the test. For me it was a back injury that occurred during a grappling session which required surgery last September. Looking back it’s easy to say I should have done more soft tissue work, anterior core exercises, mobility drills, and gotten more rest but… hindsight’s always 20/20. What is it going to take for me to get healthy? Strengthening the right muscles, mobilizing the right joints, and training the neuromuscular system appropriately. Sounds eerily like training for performance...

I realize now that I am interested in health (specifically musculoskeletal health), because it goes hand in hand in optimizing athletic performance, but I still have to disagree with a blanket statement like “sports are healthy.”

Even a sport like distance running boasts a participant injury rate upwards of 70%! The next time you watch a baseball or softball game watch the pitcher’s shoulder as he/she pitches. Try and convince me that they throw this way to improve their health.

However, despite the risk of injury there are many reasons why I believe sports are awesome, and most of these reasons are not necessarily health related. Growing up my Dad always told me that I would learn more from playing sports than I would learn in the classroom, and I’m pretty sure he was right (but I went to class too…). I learned what it meant to work hard towards a goal, work with others, and make sacrifices for the benefit of the team. Not to mention it’s FUN, and I’ve had some of my most memorable moments on a lacrosse field or a grappling mat.

Basic Speed Development Program

The overwhelming request we get almost daily: Do you guys do speed training?

My answer: Hellz YES!

In an effort to compliment my running related warnings over at StrongGirlsWin.com from earlier today, I wanted to take this post to another level and get all geeked-out over some real-deal sprint training.You gotta present both sides of the coin, ya know?

While I've termed this post as "basic speed development," please DO NOT confuse that for BEGINNER speed development. There's a big difference. This sample program is for someone who has at least a year of regimented general training under their belt that is heavy on both sprint and weight training fundamentals.

Without further delay...

Basic Speed Development Program

- Day 1 - Starts, Speed, & Total Body Lift with Lower Body Emphasis

- Day 2 - Tempo Run

- Day 3 - Special endurance & Total Body Lift with Upper Body Emphasis

- Day 4 - Tempo Run

- Day 5 - Starts, Speed Endurance, Long jump/triple jump Technique (at high intensity and include as overall daily volume), & Total Body Lift (even split)

- Day 6 - Tempo Run

- Day 7 - Rest

Notes:

- Keep your intensity above 90% or below 65%! The in-between work is trash for developing true speed and will only increase the likelihood for injury, while decreasing the chance for improvements.

- Avoid the pitfalls of starting with high volume and low intensity. Rather begin with HIGH INTENSITY and LOW VOLUME. Then gradually increase volume while keeping the intensity high.

Sample Program Details:Monday - Speed Work: 2 x 3 x 20-30m accelerations (rest at least 4-minutes between reps); Med Ball Throws @ 6-10lbs: Squat to Overhead Push Throw x 6-8 + Keg Toss x 6-8 (at least 1-minute rest between each throw, we're after MAX EFFORT with every single toss/throw); Weights: Total body lift with lower body emphasis; Core: 100 reps (choose whatever floats your boat) Tuesday - Tempo Run: 8-12 x 100m (easy, basically a fast jog) + complete 10-20 V-Ups (or whatever core work you prefer) between each run - use the runs as the recovery between the V-ups Wednesday - Special Endurance: 2 x 150-300m with 20-25 min recovery; during the recovery (every 7-8 mins) do some light tempo runs, body weight calestenics, core, etc. the goal here is to simply stay warm during the break; Weights: Total body with upper body emphasis; Core: 200 reps (choose whatever floats your boat) Thursday - Tempo Run: Similar to Tuesday Friday - Speed Work: 2 x 3 x 20-30m accelerations (rest at least 4-minutes between reps); Med Ball Throws @ 6-10lbs: Squat to Slam x 6-8 + Falling Forward Chest Throw to Sprint x 6-8 (at least 1-minute rest between each throw, we're after MAX EFFORT with every single toss/throw); Weights: Total body lift (even split); Core: 100 reps (choose whatever floats your boat) ***After several weeks, longer sprints (50-60m) can be added to the speed workouts on Mondays and Fridays.

Good luck, may the Force be with you...

Get it? Force...

...I already said I was getting geeked-out over this one, so I think that was a pretty solid joke.

Bridging the Gap Between Rehab and Sports Performance Training

This morning, Sarah and I are meeting with a local physical therapy clinic, in order to discuss working together to better serve our athletes and clients. This reminded me of an article of mine that was published a couple years ago over at ElitefTS.com, that many of you may not have seen yet.

Bridging the Gap Between Rehabilitation and Sports Performance Training

One of the things we at SAPT pride ourselves in, and something that separates us from surrounding training facilities, is our ability and genuine desire to help people train around injuries they are currently experiencing and/or just coming off of. On top of this, we are well aware of the fact that if injured athletes fail to immerse themselves in a sound, science-based resistance training regimen immediately following physical therapy, the odds are quite high they'll be right back in the PT clinic, or, even worse, on the surgeon's table.

However, we also realize that we are not physical therapists, nor do we pretend to be. Which is why we seek to form and maintain symbiotic relationships with PTs. When the strength coach and physical therapist each work within their own, unique sphere of expertise, while simultaneously collaborate with one another, the athlete/client will be in much better hands than if they neglected either of the two options.

Anyway, while it's not the most "sexy" of topics, the article above dives into some practical solutions for the strength coach, physical therapist, and (most importantly) the injured athlete.

Are You Really Squatting Correctly?

We all know the cue of “drive your knees out” when squatting but have you ever had someone observe your squat or watched yourself on camera when squatting? If you haven’t you’d be surprised to find out that your knees are probably tracking incorrectly. When coaching the squat to our athletes and clients for the first time I notice two things that happen. The first thing is the knees just do not drive out at all leading to improper tracking and you get something that looks like this…

[vsw id="AabLx4YvJvg&list=UUKSYQ75Buogznl62rdbks2Q&index=3&feature=plcp" source="youtube" width="425" height="344" autoplay="no"]

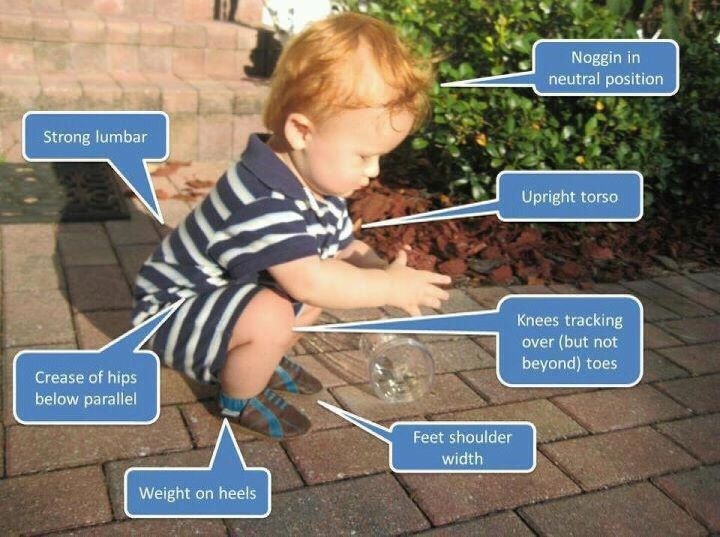

As you can see from the video the knees never track with the middle of the feet and you are left with a continuous valgus collapse. This is due to a number of reasons (poor glute strength, lack of body awareness, tight adductors) but mostly because people grow out of the habit of squatting correctly because they simply stop doing it over the years. Yes, it is true that if you don’t use it you lose it. We all at one time possessed the ability to squat correctly we just don’t do any up keep and then quickly forget how to do it.

Anyways, after seeing this I'll tell the person for the next set that as they lower they need to actively drive their knees out or “towards the wall”. This is when I notice the second thing that typically goes wrong during a squat which you can observe from the video below.

[vsw id="_Vuw15qlRfg&list=UUKSYQ75Buogznl62rdbks2Q&index=2&feature=plcp" source="youtube" width="425" height="344" autoplay="no"]

This time you’ll see that yes the knees actively drive out but they drive out way to much at the beginning, they will shoot in as they get close to the bottom, then will shoot in once they switch to the concentric portion. Cue face in palm…

So what do you do now? When it comes to this I will simply ask the person what they feel is going on with their lower body throughout the movement. Undoubtedly they will say it feels weird or it feels like they are actively driving their knees out. I’ll go on to tell them what is actually going on and/or film them to show them. Most of the time I don’t need to film because I will explain what I want to see happen on the next set. I'll say, “On the next one I don’t want you to drive your knees out until you feel you are half way down. Once you feel you’re about half way I want you to really overcompensate by driving your knees out about twice as hard as you feel you need to”. What I’ll get out of this is exactly what I was looking for which is the knees tracking with the “middle” toe of the foot throughout the whole movement as you can see in the video below.

[vsw id="OoqbgRL_0XA&list=UUKSYQ75Buogznl62rdbks2Q&index=1&feature=plcp" source="youtube" width="425" height="344" autoplay="no"]

It’s amazing how well this has worked but also a little crazy. It takes someone literally trying to overcompensate twice as much from what they think “feels right” in order to get them to squat correctly. I’ll ask the person how that felt and they will always say “really weird!” My immediate response is well that’s actually exactly what it should look like and eventually the more you do it the more it will start to feel right.

I encourage you to have someone look at your squat who knows what they are doing or have someone record you so you can make sure you are squatting correctly. If your knees aren’t tracking correctly you probably won’t get much stronger and you will also be setting yourself up for injuries later on.

Hope this helps!

Get a Massage: Research Backs it Up!

My amazing spouse surprised me with a short getaway this past weekend. He coordinated everything: Arabella’s weekend care, room at the Gaylord in the National Harbor, meals, and – what I want to focus on – a massage. It’s been a while since I had a really good massage. My last one was also a pregnancy massage, which I thought was a bit too light – I mean, just cause I’m pregnant, doesn’t mean I’m not training. So, I was pleasantly surprised when this therapist really started digging into the muscle adhesions.

She effectively addressed my trouble areas: upper back, lower back, and calves. Plus, found an unexpected problem area in my lateral deltoids.

Ryan’s therapist attacked the root of his elbow tendonitis by working on his forearms and, hopefully, reiterated (in his mind) the importance of soft-tissue care for this type of ailment.

This experience got me thinking about all the benefits that have been proven to be associated with massage:

Are you an athlete with athsma? If so, read this… a little massage will likely improve your pulmonary function (and, bonus alert, feel amazing):

Pulmonary Functions of Children with Asthma Improve Following Massage Therapy. Objectives: This study aimed at evaluating the effect of massage therapy on the pulmonary functions of stable Egyptian children with asthma. Design: This study was an open, randomized, controlled trial. Settings/location: The study was conducted in pediatric allergy and chest unit of the New Children's Hospital of Cairo University, Egypt. Subjects and interventions: Sixty (60) children with asthma were divided randomly into two equal groups: massage therapy group and control group. Subjects in the massage therapy group received a 20-minute massage therapy by their parents at home before bedtime every night for 5 weeks in addition to the standard asthma treatment. The control group received the standard asthma treatment alone for 5 weeks. Outcome measures: Spirometry was performed for all children on the first and last days of the study. Forced expiratory flow in first second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1/FVC and peak expiratory flow (PEF) were recorded. Results: At the end of the study, mean FEV1 of the massage therapy group was significantly higher than controls (2.3±0.8 L versus 1.9±0.9 L, p=0.04). There was no significant difference in FVC (2.5±0.8 L versus 2.7±0.7 L, p=0.43). However, FEV1/FVC ratio showed a significant improvement in the massage therapy group (92.3±21.5 versus 69.5±17, p<0.01). PEF difference was not significant (263.5±39.6 L/minute versus 245.9±32 L/minute, p=0.06). Conclusions: A beneficial role for massage therapy in pediatric asthma is suggested. It improved the key pulmonary functions of the children, namely, FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio. However, further research on a larger scale is warranted.

No, asthma? Just a regular ol’ person? This study indicates all kinds of great biologic effects:

A Preliminary Study of the Effects of a Single Session of Swedish Massage on Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal and Immune Function in Normal Individuals. Objectives: Massage therapy is a multi-billion dollar industry in the United States with 8.7% of adults receiving at least one massage within the last year; yet, little is known about the physiologic effects of a single session of massage in healthy individuals. The purpose of this study was to determine effects of a single session of Swedish massage on neuroendocrine and immune function. It was hypothesized that Swedish Massage Therapy would increase oxytocin (OT) levels, which would lead to a decrease in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) activity and enhanced immune function. Design: The study design was a head-to-head, single-session comparison of Swedish Massage Therapy with a light touch control condition. Serial measurements were performed to determine OT, arginine-vasopressin (AVP), adrenal corticotropin hormone (ACTH), cortisol (CORT), circulating phenotypic lymphocytes markers, and mitogen-stimulated cytokine production. Setting: This research was conducted in an outpatient research unit in an academic medical center. Subjects: Medically and psychiatrically healthy adults, 18-45 years old, participated in this study. Intervention: The intervention tested was 45 minutes of Swedish Massage Therapy versus a light touch control condition, using highly specified and identical protocols. Outcome measures: The standardized mean difference was calculated between Swedish Massage Therapy versus light touch on pre- to postintervention change in levels of OT, AVP, ACTH, CORT, lymphocyte markers, and cytokine levels. Results: Compared to light touch, Swedish Massage Therapy caused a large effect size decrease in AVP, and a small effect size decrease in CORT, but these findings were not mediated by OT. Massage increased the number of circulating lymphocytes, CD 25+ lymphocytes, CD 56+ lymphocytes, CD4 + lymphocytes, and CD8+ lymphocytes (effect sizes from 0.14 to 0.43). Mitogen-stimulated levels of interleukin (IL)-1ß, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, and IFN-? decreased for subjects receiving Swedish Massage Therapy versus light touch (effect sizes from ?0.22 to ?0.63). Swedish Massage Therapy decreased IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 levels relative to baseline measures. Conclusions: Preliminary data suggest that a single session of Swedish Massage Therapy produces measurable biologic effects. If replicated, these findings may have implications for managing inflammatory and autoimmune conditions.

Thinking about getting a pre-event massage before your next competition? BE CAREFUL with your decision and KNOW yourself!

Psychophysiological effects of preperformance massage before isokinetic exercise. Sports massage provided before an activity is called pre-event massage. The hypothesized effects of pre-event massage include injury prevention, increased performance, and the promotion of a mental state conducive to performance. However, evidence with regard to the effects of pre-event massage is limited and equivocal. The exact manner in which massage produces its hypothesized effects also remains a topic of debate and investigation. This randomized single-blind placebo-controlled crossover design compared the immediate effects of pre-event massage to a sham intervention of detuned ultrasound. Outcome measures included isokinetic peak torque assessments of knee extension and flexion; salivary flow rate, cortisol concentration, and [alpha]-amylase activity; mechanical detection thresholds (MDTs) using Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments and mood state using the Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire. This study showed that massage before activity negatively affected subsequent muscle performance in the sense of decreased isokinetic peak torque at higher speed (p < 0.05). Although the study yielded no significant changes in salivary cortisol concentration and [alpha]-amylase activity, it found a significant increase in salivary flow rate (p = 0.03). With the massage intervention, there was a significant increase in the MDT at both locations tested (p < 0.01). This study also noted a significant decrease in the tension subscale of the POMS for massage as compared to placebo (p = 0.01). Pre-event massage was found to negatively affect muscle performance possibly because of increased parasympathetic nervous system activity and decreased afferent input with resultant decreased motor-unit activation. However, psychological effects may indicate a role for pre-event massage in some sports, specifically in sportspeople prone to excessive pre-event tension.

Outside of these few studies, there are loads of studies supporting massage for everything from improving brain development in preterm babies to care for cancer patients to treating chronic constipation.