One Way to Combine Strength and Size Training

Very rarely do I program more than five reps of of a main lift for an athlete. Why? For beginners: it helps keep technique in check and helps them to stay focused (I often see the young athlete's eyes glaze over and head turn left+right to look at other distractions once he or she passes the 5-rep mark!).

For the intermediate and advanced lifters: low reps keep recovery prompt and hold muscle soreness at bay. Having an athlete perform sets of ten to twenty on the squat would leave him/her absolutely torched come game day or time for sport-specific technique work.

Not to mention, sets of four to five reps seem to be the crossroad for muscle building and neural training. You can still pack on some size, while at the same time teaching the neuromuscular system to contract faster and with greater force.

Anyway, higher reps can still have their place in training, especially for the "Joe's and Jane's" out there simply looking to pack on some lean body mass. I have also found that some athletes respond better to higher reps, but I still want to keep the total volume in check. So, how does one go about this? How do you simultaneously train strength and size, without adding too much volume that it becomes detrimental to the nervous system?

First and foremost, be honest with yourself. If you're still a beginner (can you realistically squat 1.5x your bodyweight with perfect form yet?), and even if you've just entered into the "intermediate" portion of the continuum, don't even concern yourself with this strategy. In all likelihood your technique is going to breakdown and you'll expose yourself to injury.

Moving on, here's what to do if you're at the appropriate stage in your training:

Do a few heavy sets, and follow it up with one "back off" set of higher reps.

This way, you stimulate the high-threshold motor units via lower reps, and provide a solid strength stimulus. Then, the bodybuilder side of you can satisfy his/her craving via the "get your pump on" set at the end!

Here are a few examples:

3x5, 1x10 3x4, 1x12 2x5, 1xAMAP ("as many as possible") 3x3, 1xL2ITT ("leave two in the tank")

There are a bunch of ways to do this really. Putting the last example into a real-life example, here's something I might do....

Using chinups as the lift of choice, I may work up to a heavy set of three, but still ensuring the reps are crisp and I'm not grinding them out. So, I might work up to 110x3:

Rest a couple minutes, and then do a bodyweight set of 17-18 chins, leaving a couple in the tank (it should be obvious but just in case: that higher rep set should utilize much less weight than the heavy sets).

I find these set-rep schemes lend themselves particular well to chins, squats, pushups, and rows.

A couple caveats:

- Don't do this year round, but cycle in a few, 3-4 week blocks of this throughout your yearly training

- Be especially careful with the squats, stopping the set if you're near failure and/or are turning your squats into an ugly "goodmorning/squat" combo. The more squat videos I see on the internet, the more hesitant I become in providing public advice like this because most people's technique is atrocious at best.

- I'd avoid this high rep back-off set strategy with deadlifts as the risk:reward ratio simply isn't worth it.

That's it. You can use your imagination really....just do a few heavy sets, staying away from failure, and then back off the weight and get your pump on with one, higher rep set to finish it off.

Excellent Strategy for Upper Back Development

I really don't think there's a such thing as "too much upper back work." In fact, I'd go so far to say that undergoing a training plan (be it athletic performance training, running, bodybuilding, etc.) without paying special heed to the portion of your torso that you don't see in the mirror is akin to constructing a house on a foundation of sand.

Keeping it brief, here's a simple, truncated list of what upper back work can do for you:

I really don't think there's a such thing as "too much upper back work." In fact, I'd go so far to say that undergoing a training plan (be it athletic performance training, running, bodybuilding, etc.) without paying special heed to the portion of your torso that you don't see in the mirror is akin to constructing a house on a foundation of sand.

Keeping it brief, here's a simple, truncated list of what upper back work can do for you:

- Improve posture

- Augment your "big lift" training (upper back weakness is often a limiting factor in how much you can deadlift, squat/front squat, and bench press)

- Ward off shoulder issues

- Offset all the slouching we do on a daily basis

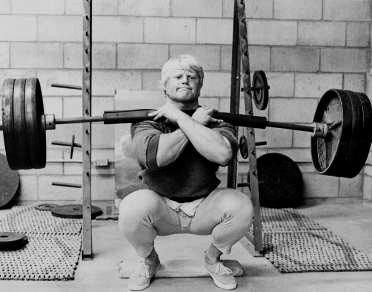

And, perhaps what most of the majority of the crowd cares about: Enhancing one's aesthetic. For the ladies in the crowd, nothing exudes more confidence than standing "tall" with the shoulders pulled back. For the men the crowd - with some added assistance from farmers carries - you can at least come close to emulating Tommy Conlon's trap/upper back development which totally PWNED in the movie Warrior (see picture on the left).

Yeah, exactly.

Alright, let's get to it. Here's an awesome strategy to give your upper back some much-needed attention:

Pair a bilateral 'pull' with a unilateral 'push,' and double the number of sets for the pulling exercise.

As soon as I heard this strategy from Eric Cressey I knew it was brilliant, and, upon implementing it in my own training, I wasn't disappointed.

What does it look like?

Pick a bilateral, horizontal pulling exercise (chest-supported row, barbell row, TRX row, cable row, etc.) and pair it with a unilateral pushing exercise (single-arm dumbbell press, single-arm overhead press, single-arm pushup, etc.). I recommend putting this pairing first during an upper body day, so the first two exercises would look something like this:

A1. Seated Cable Row, Pronated Grip

A2. SA DB Bench Press, Neutral Grip

HOWEVER, here's the kicker.....set up the set-rep scheme something like this:

A1. Seated Cable Row, Pronated Grip: 6x8 A2. SA DB Bench Press, Neutral Grip: 3x6/side

THEN, sequence the movements as follows: Seated Row --> SA Bench (left side) --> Seated Row --> SA Bench (right side) --> Seated Row --> SA Bench (left side) --> etc. etc. etc. clap yo' hands, fist pump x1,000.

I've been using this with enormous success for the past eight weeks or so in my own training. Why is this so awesome?

1. It's an easy way to keep your pulling vs. pushing volume in check. Most All of us tend to favor pressing over pulling, so setting up the sets/reps like this forces us to remain honest.

2. It's a fantastic way of getting in a lot of good horizontal pulling without feeling too fatigued. Since you essentially take a "mini break" between each set of rows to do your pressing exercise, it activates the antagonists of the back musculature, leaving you feeling a bit more rested by the time you get back to the row.

3. You're still providing plenty stimuli for the pressing muscles via the single-arm variation. Not to mention, the single-arm pressing exercise is an excellent method of receiving the added benefit of core stability training. Your have to brace your abs and glutes HARD to keep your torso from shifting side to side. (Note: If you're wondering why I have my arm out to the side like an idiot in the video, it's 'cuz I'm trying to counterbalance. Don't knock it till you try it....geeze....)

4. It just flows well. You can knock out this pairing in relatively little time while still getting a lot of work accomplished.

To put things in perspective, let's say you just do this during one of your upper body days for two, 4-week training blocks. Assuming you keep all your other pull/push pairings of equal volume (which I wouldn't...but let's just go with it...), that gives you an extra 240 reps of pulling over a mere 8-week period! Just by making that simple adjustment in your programming.

Even if you go with a "6x6" set-rep scheme for the bilateral pull, that still gives you 144 more repetitions of pulling over pushing, and we're talking only two months out of the year.

As long as you keep up with your deadlifts and other cornerstone lifts for the backside, imagine what will happen if you cycled this in and out of your training year round?

5 Quick & Random Training Tips

1. How and when you do your abdominal training in a given week is actually fairly important. For example, if you decide to do standing rollouts 24-48 hours before a heavy deadlift session, chances are your deadlifts are going to suffer greatly, and perhaps even be risky to attempt (it will be much more difficult to stabilize your lumbar spine).

This is because rollout variations place incredible eccentric stress on the anterior core, inducing large amounts of soreness and requiring a longer recovery period. The only caveat to this rule would be if your name is Ross Enamait.

This is because rollout variations place incredible eccentric stress on the anterior core, inducing large amounts of soreness and requiring a longer recovery period. The only caveat to this rule would be if your name is Ross Enamait.

Other abdominal programming faux pas I can think of would be pairing an anterior loaded barbell variation (i.e. front squat or zercher grips) with an ab exercise, and/or placing a hanging leg raise before or alongside a farmers walk. The former is a blunder because anteriorly loaded barbell movements already place considerable demands on the core musculature; the latter isn't the greatest idea because your grip endurance is going to become an issue. Spread them apart to receive the maximum benefit of each.

2. If squatting is problematic for you, you don't need to force it. At least not initially. While the squat is a phenomenal movement and undoubtedly should be a staple in one's strength and conditioning program, I'm finding that more and more people need to earn the right to back squat safely, much like the overhead press. This may be due to structural changes (i.e. femoroacetabular impingement) or immobility (i.e. poor hip flexion ROM or awful glenohumeral external rotation and abduction).

If this is the case, simply performing a heavy single-leg movement as the first exercise in the session will work perfectly. You can use anything from forward lunges to bulgarian split squats, but my favorite is probably the barbell stepback lunge with a front squat grip.

You're still receiving the benefits of axial loading due to the bar position, you can still receive a healthy dose of compressive stress in your weekly training (if you're deadlifting), and yes, you'll still be exerting yourself. I recommend performing these in the 3-6 rep range to allow for appreciable loads.

And, keep in mind, when I said "if squatting is problematic" at the beginning of point #2, I was referring to structural, mobility, and/or stability abnormalities that may make it unsafe for you to squat for the time being. I wasn't, of course, implying that if it's "just too hard" that you shouldn't do it. There's a pretty thick line between one being contraindicated for an exercise and someone who's simply unwilling to to do a lift because it takes mental+physical exertion.

3. If your wrists bother you while doing pushups, try holding on to dumbbells. It will take your wrist out of an extended position into more of a neutral one, greatly reducing the stress on that joint.

I also like holding on to dumbbells because they allow you to use a "neutral grip," thus externally rotating the humerus, giving your shoulder more room to breathe.

I also like holding on to dumbbells because they allow you to use a "neutral grip," thus externally rotating the humerus, giving your shoulder more room to breathe.

4. Think twice before consuming dairy as your pre-workout fuel. This may seem obvious, but frankly I still talk to people who consume cereal before a morning workout, or down milk shortly before an evening training session. Your stomach isn't going to like this while doing chest-supported T-Bar rows, anti-extension core variations, or anything for that matter.

Another tip: don't shove a bunch of doughnuts down your pie hole before training. I thought this one would be no-brainer, but I actually had a kid vomit after pushing the prowler at a sub-maximal intensity. Upon asking him what he ate beforehand, he said, "Umm, well nothing all day, and then I ate a bunch of doughnuts before coming here." Fail.

5. Figure out for yourself what training split is best for you personally. For example, I feel that training upper body the day before lower body affects me (negatively) more than if I do it the other way around. However, I know others who feel the exact opposite. Also, for those of you who utilize a bodypart split, and train deadlifts on "back day," be sure to take into consideration when and how you'll do squats on "leg day," due to the beating your spine will receive from both exercises.

Which mass-gaining method is "best"?

After dragging my brain through 41 pages of research on "The Influence of Frequency, Intensity, Volume and Mode of Strength Training on Whole Muscle Cross-Sectional Area in Humans" guess what the conclusion was on an extensive study designed to figure out the best way/combination of ways to increase muscle mass? Essentially, that all variables are valuable and there is NO ONE SINGLE MAGIC BULLET.

Sometimes - okay, a lot of times - research totally cracks me up. I think I've stated this before. This paper was about 10x longer than most with extreme detail and for what... to confirm something that any experienced strength coach knows:

Regarding progression, we recommend low volumes (e.g. 1–2 sets) in the initial stages of training, when performing eccentric-muscle actions, because low volumes have been shown to be sufficient to induce hypertrophy in the early stages of training and because exercise adherence may be improved if the workout is relatively brief. Also, avoiding unnecessary damage may allow hypertrophy to take place earlier. As the individual adapts to the stimulus of strength training, the overall volume and/or intensity may have to be gradually increased to result in continued physiological adaptations and other strategies (e.g, periodisation) can also be introduced if even further progress is desired.

So, through actual published research (and not the usual anecdotal evidence), it is confirmed that the best policy when progressing an individual for anything - in this case hypertrophy - is always found in moderation.

The next time you're considering ordering any number of TV products promising to solve all your problems or thinking about signing your kid up for training that "guarantees" quick results, I ask that you keep in mind some solid research and accept that anything worthwhile in life takes time, hard work, and guidance.

A Little Sage Advice on Program Design: Is Exercise Selection Really the Most Important Programming Variable?

When most people think about designing training plans, they think of the process as nothing more than a matter of choosing which exercises they are going to do on a given day. This may work for a little while, but what happens when progress begins to slow, or if you"re working with an athlete or client that only has twelve weeks to maximize their physical preparation? Can you just slap a bunch of exercises down, hoping it will work?

Or, even if you"re just seeking to look better and move better, and you"re spending 3 hours a week in the gym, don"t you want to know that your time is being optimally invested, and not spent?

Treating exercise selection as the most important programming variable can be quite the imprudent approach, given that exercise selection is only ONE piece in the programming puzzle; and, in fact, is probably the last on the list.

Let"s look at the list of variables you have to "play with" when you sit down to create a program:

- Training Type. Examples of training type would be jumping exercises, running exercises, change-of-direction work, resistance training, and skill work (ex. practicing your sport-specific drills, such as hitting a baseball, or drilling hip escapes and passing an open guard in Jiu-Jitsu). This must be decided first.

- Intensity (neural, muscular, mental, and metabolic factors)

- Volume

- a. Number of Reps

- b. Number of Sets

- Tempo

- Rest Periods

- Exercise Selection

As you can see, exercise selection is last on the list! Not only that, but there are quite a number of critical factors before exercise selection.

Much more important than the exercises you choose is HOW you choose them to impose a specific demand to each of your body"s systems, creating the desired training effect.

To help make my point....what if I told you that the same exercise can be applied in completely different ways, thus developing diverse adaptations and ultimately leading to an entirely different result?

Take the squat, for example. By manipulating the loading, repetitions, sets, tempo, and rest periods for just that one exercise, we can create entirely different adaptations:

- Maximal Strength

- Alactic Power Output

- Aerobic Anaerobic Endurance

- Static Strength

- Explosive Endurance

- Aerobic Power Recovery Rate

- Lactic Capacity

And, because I"m cool like that and am feeling a tingling sensation within my "giving spirit" with the holiday season upon us, I"ve provided you a few video examples:

Maximal Strength

While there"s some wiggle room here, this method is used performing 1-5 reps with a heavy load; the purpose being to stimulate the nervous system to improve maximal muscle recruitment. Here is Ryan hitting a 375lb squat on Thanksgiving morning:

**Aerobic Anaerobic Endurance; Static Strength

With a tempo squat, you enhance the body"s ability to delay fatigue, maintain power output over an extended period of time, improve anaerobic endurance, and develop static strength. This would be important for endurance athletes, military personnel, fighters, and yes, even field athletes.

Here I am using a 2-0-2 tempo...two seconds down, no pause at the bottom, two seconds up, and no pause at the top (I am admittedly performing the concentric portion a bit too quickly in my demo). Constant tension and slow movement is key here:

**Aerobic Power

With a squat jump, and using the right work:rest ratio, you can augment the fast twitch fibers ability to produce maximal power over a longer period of time. You can also train them (the type II fibers) to recover casino online more quickly betwixt explosive bursts of high power output:

*Imperative Note: Do NOT even bother with squat jumps (let alone loaded squat jumps) until you can squat at least 1.5x your body weight with good form*

Lactic Capacity

With a static dynamic squat you you can help your body learn to delay fatigue by boosting the buffering mechanisms of the lactic energy system. Do two reps, then hold in the stretched position for ten seconds, then two more reps, then hold for ten seconds, etc. etc. etc. One set of these babies should last 3-5 minutes! (Hint: this equals MAJOR suckitude). Work your way up to 10 minutes with a light weight, then slightly increase the weight and go back to 3 minutes per set:

**With the tempo squats and squat jumps, it is of extreme importance you utilize the correct number of sets along with the proper work:rest ratio to elicit the correct adaptation. Don"t just go hog wild here. You must also be sure you place them in their proper context within the grand program design structure, and know how/when to use them; however, I"m not going to delve into that now.

As you can see, the basic squat can be used for a myriad training tools, and the demos I gave are just the tip of the iceberg. Nonetheless, I hope that this at least helped you understand that good program design is much more than slapping down exercises on paper. A squat performed with a particular load, tempo, number of reps, number of sets, tempo, and specific rest period will evoke an entirely different adaptation than doing a squat with a different all-of-those-things-I-just-listed.

When I write programs, the actual exercise is usually the LAST thing I put down on the paper; I decide how I"m going to manipulate the first five variables on the list above, THEN I put down the exercise I want to use to obtain the desired training effect; be it for someone training SAPT or in my own training.

Understanding Competing Demands, Part Deux: A Sample Workout

On Wednesday, I touched on competing demands and how these will affect the quantity, and quality, of the training stressors appropriately applied to athletes and general fitness enthusiasts alike. I used myself as an example of making a major mistake in attempting to obliterate a great athlete while not understanding everything he was facing outside the gym walls of SAPT. You can read it here in case you missed it. Getting right to it, below is a sample lower body workout I may use with an athlete who is performing sprints and change-of-direction training with his or her sports team, throwing/hitting two days per week, and maybe getting in a lift or two under the watch of his high school coach. There are obviously countless scenarios that would affect the individualized programming of the specific athlete, but the one below should at least give you an idea.

A) Trap Bar Deadlift

*

1x3, then 1x3@90% weight used in set 1

B1) DB Split Squat ISO Hold B2) ½ Kneeling SA Cable or Band Row

**

2-3x5/side hold :5

3x8/side

C1) DL Hip Thrust, Back+Feet Elevated

***

C2) Sandbag Walkover C3) Side-Lying Wallslide with Slider

2x8 hold :5 2x6 2x8/side

D) Sledge Swings or EASY Prowler Push

2-3x10/side or 3 Trips

*Work up to one "heavy" set of three, and then do one more set of three at 90% of the last weight used. **Even though this session would be considered "lower body," I added this because I really feel people can't get enough horizontal pulling. Especially with the unilateral version you receive a bit of added core stability and thoracic mobility to boot. ***Your butt cheeks should feel like they're about to fall off the bone if you do these correctly.

B1) Split Squat ISO

B2) 1/2 Kneeling SA Band Row

C1) DL Hip Thrust, Back+Feet Elevated

C3) Side-Lying Wallslide with Slider

D) Sledge Swings

The above program will provide plenty training stimulus to elicit positive strength adaptations, while at the same time not fatiguing the athlete to the point of sending him or her backwards. Also, while I didn't list them, there would also be plenty of mobilization drills to help "undue" the crappy positioning and imbalances that the athlete accrues throughout the week.

With the trap bar deadlift, you'll receive a solid dose of work for the entire posterior chain while still giving the quads plenty stimuli (as the trap bar deadlift engages the quads a bit more than conventional deads), along with some healthy compressive stress (which the spine tends to handle better than shear stress).

The accessory work will hit most of the things that athletes fail to receive from their other spheres of training, namely:

- Glute strength and endurance (which, unless you're first name is Don, and last name Juan, there's about a 110% chance you lack these)

- Scapular retraction and depression

- Serratus anterior work

- The lateral subsystem (QL, adductor complex, and glute medius)

- Light conditioning (with the sledge or prowler) that should "wake-up" the athlete more than anything as opposed to some insane glycolytic session

In all honesty, I tried to come up with a clever way to end this post but...I got nothin'.